There they go again – the repeated delusions of the techno-accelerationists (part three)

In the 1970s, we were told to ignore warnings of environmental and social collapse. As those warnings come true, once again we are being told that ‘technology’ will come to our rescue.

Source: https://playgroundai.com/post/retrofuturism-vintage-sci-fi-poster-from-50s-retro-car-ba-cln2qvtjw02cws601a1gjqelr

In the 1970s, we were told to ignore warnings of environmental and social collapse. As those warnings come true, once again we are being told that ‘technology’ will come to our rescue.

This is the third part of a three-part post which draws on one chapter of my most recent book.

You can find the first post here, in which we discussed the rise of a critical environmental consciousness in the late 1960s and early 1970s that had started to challenge foundational ideas about contemporary industrial capitalism, and the second post here, in which we discussed the subsequent conservative and corporate fightback.

Events helped the anti-environmental right as well. In 1973 (and later in 1979, under Carter), the major middle eastern oil-producing nations embargoed supplies to the U.S., causing higher prices for gas and shortages at gas stations. People waited hours to fill up their cars. To environmentalists, the ‘crisis’ proved their point; we’d become accustomed to consuming seemingly abundant natural resources, and this needed to change. Much greater conservation of scarce resources and the development of alternative energy sources were urgently required.

The corporate-funded new right had other ideas. The energy crisis super-charged their arguments. Government needed to get out of the way, stop setting prices and imposing environmental regulations, and allow corporations to meet demand (the free-market economist Milton Friedman frequently promoted this argument in newspaper op-ed pages).

Such commentators were helped by deindustrialization and faltering standards of living, allowing them to frame the argument as ‘jobs versus the environment’, even that regulation was against the ‘American way of life.’

To many people, it was an attractive message: no-one had to change their behavior, and something else would take care of the problem. As president, Carter had criticized self-indulgence and consumption, and preached conservation and personal sacrifice. But Reagan would argue that “There are no great limits to growth because there are no limits of human intelligence, imagination and wonder” – and no need to believe the false prophets of doom either, since “…their pervasive pessimism is anti-technology [and] anti-industry.”

(At the same time, it’s also true that, as Kate Aronoff wrote in The New Republic, Carter’s commitment to austerity and ‘sacrifice’ undermined his administration, and we can say arguably heightened the appeal of Reagan’s ‘no limits’ rhetoric.)

And so as Rick Perlstein emphasizes in his work on the emergence of Reaganite conservatism (among them, Reaganland: America’s Right Turn 1976-1980, published in 2021), this seemingly unboundedly optimistic message – a reaction to analyses such as The Limits to Growth and growing environmental concern – was crucial to Reagan’s appeal and so the rise of the new right overall.

So began what Charles Reich would later call the “un-greening of America”. The first executive order Reagan would issue as president abolished all price controls on energy. He even removed the solar panels that Carter had had installed on the roof of the White House, and denounced what he called ‘solar socialism’ (government support for developing renewable energies).

Decades, and much momentum, were lost. Reagan’s ‘free markets’ did not deliver alternative energy sources (of course, they were never really meant to); it took other governments around the world (most notably, Germany and then China) to bring down the cost of, for example solar, to the point that it is often now the cheapest form of energy.

Thus a political project that masqueraded as being ‘pro-progress’ was actually its opposite, and the very delay that the likes of The Limits to Growth (discussed in the first post) had warned about. We’re now living the results, of increasing climate chaos and all of the political, social, and economic dislocation that follows in its wake. It’s worth noting that most of the scenarios in The Limits to Growth predicted that industrial output would start to decline in the 2020s, with population declining in the 2030s – in other words, contrary to its vocal critics, the study hasn’t been disproved, rather its predictions are increasingly coming true pretty much right on time.

Which brings us to today’s ‘techno-optimists’, who in many ways merely represent a re-phrasing of what helped to get us into the current crisis (or more accurately, crises). Yet again, they are a reaction (a fundamentally conservative one, however they might describe their own politics) to rising general alarm over climate change and a growing recognition that it’s rampant industrial capitalism that got us here. And yet again, their only promise is the possibility of another ‘great acceleration’ – if only the prophets of doom and meddling governments get out of the way.

Really though, much like we saw with their predecessors in the 1970s, what today’s techno-optimists are critical of is democracy – that through growing public awareness and concern, we might actually demand that governments take action to help resolve or at least mitigate these crises. As Elizabeth Spiers wrote in The New York Times in response to Silicon Valley venture capitalist Marc Andreessen’s Techno-Optimist Manifesto, published last October:

“Neoreactionary thought contends that the world would operate much better in the hands of a few tech-savvy elites in a quasi-feudal system. Mr. Andreessen, through this lens, believes that advancing technology is the most virtuous thing one can do. This strain of thinking is disdainful of democracy and opposes institutions (a free press, for example) that bolster it. It despises egalitarianism and views oppression of marginalized groups as a problem of their own making. It argues for an extreme acceleration of technological advancement regardless of consequences, in a way that makes “move fast and break things” seem modest.

…[But] The argument for total acceleration of technological development is not about optimism, except in the sense that the Andreessens and Thiels and Musks are certain that they will succeed. It’s pessimism about democracy – and ultimately, humanity.”

There they go again. But this time, forewarned, we don’t need to go with them.

Come With Me If You Want To Live: The Future as Foretold in Classic Sci-Fi Films, is out now from Lexington Books. You can read more about it here.

There they go again – the repeated delusions of the techno-accelerationists (part two)

In the 1970s, we were told to ignore warnings of environmental and social collapse. That many people did was the result of a concerted corporate-funded fightback against a rising, critical environmental consciousness.

In the 1970s, we were told to ignore warnings of environmental and social collapse. Once again, we need to resist the fantasy that technology will resolve our problems.

This is the second part of a three-part post which draws on one chapter of my most recent book. You can find the previous post here, in which we discussed the rise of a critical environmental consciousness in the late 1960s and early 1970s that had started to challenge foundational ideas about contemporary industrial capitalism. There had to be a fightback, and there was.

The landmark environmental report The Limits to Growth (1972) had provoked particularly strong reactions – from crude dismissals of alleged alarmism, to seemingly more reasoned assertions that technology would save us. Some of the most strident criticisms came from economists, who claimed that the study underestimated the power of the technological fixes humans would invent. If resources ran low, we’d simply discover more or develop alternatives.

For example, writing in The New York Times in April 1972, Peter Passell, Marc Roberts, and Leonard Ross dismissed The Limits to Growth as an “empty and misleading work.” Instead, they argued that previous technological advances had demonstrated that we can deal with scarcity by dramatically reducing exploration and extraction costs, and substituting plentiful materials for scarce ones. So, no problem (or problematique - which was The Limit to Growth’s term for the multiple, inter-related crises it described).

Coal power plant in the 1970s

In fact, The Limits to Growth team had tested this. They gave their model unlimited, non-polluting nuclear energy and doubled reserves of non-renewables. All the same, the population crashed when industrial pollution soared. Then they reduced pollution significantly; this time, the crash came when we ran out of farmland. Higher farm yields and birth control helped, but soil erosion and pollution were still unavoidable. The core problem remained, that of exponential growth. Only when industry and population growth were constrained, and all the technological fixes applied, did the model stabilize.

Nonetheless, economists continued to claim that The Limits to Growth ignored how technology can ensure that resources expand to meet demand. For example, the libertarian right leaning economist Julian Simon argued in books such as The Ultimate Resource (1981) that societies have ‘natural’ feedback systems, one of which is technological innovation in the face of scarcity (Simon even claimed we will have enough resources to last 10 billion years).

This story, of The Limits to Growth and the pushback it received, is fairly well known. But what has been neglected is how, in reaction, critical environmentalism helped to bring together the right into a new political force – one that included a strong critique of the left’s supposed anti-technologism, and that argued that a much more optimistic belief in technology is required to create the future.

To begin with, appropriately, many conservatives supported conservation efforts, and as noted, important environmental legislation was passed under a Republican administration. But some thinkers saw something much more sinister in the rising environmental consciousness. For figures such as Ayn Rand, with her strongly anti-statist libertarian philosophy, the environmental left would lead to an immiserated, totalitarian future. In her 1971 essay collection The New Left: The Anti-Industrial Revolution, Rand argued that ‘ecology’ was a Trojan horse being used to propel the world back to a new Dark Ages. She was also skeptical about environmental peril, calling it an “artificial, PR-manufactured issue, blown up by the bankrupt left”.

Ayn Rand - self-proclaimed “radical for capitalism”

Rand might have been extreme. But as parts of the environmental movement became more critical of contemporary industrial capitalism, more of the right shifted towards to her view. Nor was this interpretation wholly wrong – the logic of environmentalism and analyses such as The Limits to Growth effectively were an emerging challenge to contemporary capitalism, and had to be resisted.

In 1971, future Supreme Court Justice Lewis Powell Jr. sent a memo to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce (titled Attack on American Free Enterprise System), urging the ‘apathetic’ business community to organize against spreading anti-corporate feeling (Powell cited Reich’s The Greening of America, discussed in the previous post, as exemplifying this ‘dangerous’ sentiment):

“[W]hat now concerns us is quite new in the history of America. We are not dealing with sporadic or isolated attacks from a relatively few extremists or even from the minority socialist cadre. Rather, the assault on the enterprise system is broadly based and consistently pursued. It is gaining momentum and converts.”

The Powell memo

Business needed to engage in politics, shape public opinion, initiate court cases, create think tanks, and influence university courses – all of which they subsequently did. To Powell: “[P]olitical power is necessary; …such power must be assidously [sic] cultivated; and …when necessary, it must be used aggressively and with determination.”

As a consequence, often funded by extractive, polluting industries, this new right would argue that the environmental left had fabricated an ecological crisis as a means of destroying capitalism and seizing power. By the end of the 1970s, anti-environmentalism had become a defining feature of American conservatism.

What happened next would change the future – the one we’re living in now (as we’ll discuss in the final post).

Come With Me If You Want To Live: The Future as Foretold in Classic Sci-Fi Films, is out now from Lexington Books. You can read more about it here.

There they go again – the repeated delusions of the techno-accelerationists (part one)

In the 1970s, we were told to ignore warnings of environmental and social collapse. Once again, we need to resist the fantasy that technology will resolve our problems.

In the 1970s, we were told to ignore warnings of environmental and social collapse. Once again, we need to resist the fantasy that technology will resolve our problems.

This is the first part of a three-part post which draws on one chapter of my most recent book.

In a U.S. presidential election year in which we might be ‘treated’ to at least one debate between the (historically unpopular) candidates, we’ll also likely be reminded of notable debate moments from the past.

One of the most famous was Ronald Reagan’s “There you go again”.

The 1980 presidential election looked like it was going to be close. The incumbent, Jimmy Carter, had struggled in his first term, with events both domestic (the energy crisis, simultaneous inflation and recession) and international (the Iranian hostage crisis, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan). But his challenger, Ronald Reagan, a former governor of California (and of course, actor and corporate spokesman before he entered politics), was regarded by many voters as too conservative, and too old.

The second debate between the candidates was held a week before election day. At one point, Carter attacked Reagan's record on Medicare, stating that Reagan had voted against it. Reagan chuckled, and then delivered his now famous (rehearsed) reply.

It’s since become part of the political lexicon, a way to suggest that an opponent is engaged in hyperbole or even hysteria (in fact, Carter was correct – soon after the election, Reagan did try to cut Medicare).

Just a week later, Reagan won in a landslide, achieving 50.7 percent of the popular vote and 489 electoral votes, with Carter trailing badly with just 41 percent and 49 electoral votes (John B. Anderson, an independent candidate, got 6.6 percent). The Reagan revolution had begun.

Reagan would use the line in a few debates over the years (other politicians have copied it as well, right up to recent elections). Reagan’s ‘happy warrior’ persona obviously proved much more popular than Carter’s often self-critical seriousness.

But it wasn’t just a matter of a personal style. The change of administration led to a profound shift in policy towards the environment, amongst many other things, one that we are still experiencing the effects of today. The philosophical differences between Carter and Reagan are also echoed in a debate that has recently resurfaced about environmental limits versus ‘technological optimism’, one that will again determine our future. To coin a phrase, here we go again.

To understand the present – and possibly to avoid making the same mistakes – we need to understand the past (which is what we’ll do in these posts).

The 1970s had seen a rising, and increasingly critical, environmental consciousness, including in the United States. In the late 1960s and early 1970s campaigns had pushed, successfully, for cleaner air and water standards, including those passed under Republican president Richard Nixon. There was even growing awareness of the threat of carbon dioxide causing ‘global warming’ (we know now that corporations such as Exxon were more than aware of the threat but kept this hidden).

These concerns were also reflected in popular culture, for example in environmentally conscious science fiction films such as Silent Running (1972), Soylent Green (1973), and Z.P.G. (1972, and an abbreviation of zero population growth), and their predecessors Planet of the Apes (1968) and 2001: A Space Odyssey (also 1968).

Although to begin with few in the new left (such as student protestors against the Vietnam War) were environmentalists, they shared a number of concerns with the growing green thinking, among them criticism of a machine-like industrial-political system leading us to destruction, the apparent insanity of the establishment, and the need for a cultural, not just political, revolution.

One popular book that brought together environmental consciousness and the counterculture was Charles Reich’s The Greening of America (1970). Subtitled How the Youth Revolution is Trying to Make America Livable, it first came to prominence as a lengthy excerpt in The New Yorker magazine and soon became a number one nonfiction bestseller, dominating The New York Times charts for 36 weeks and going on to sell two million copies.

Alongside this growing public consciousness, left intellectuals such as Herbert Marcuse, Murray Bookchin, and Paul Goodman, advanced critiques of industrial society and its dysfunctional relationship with an exploited nature (and our alienated selves). Environmental economists, such as Herman Daly, E. F. Schumacher, and Barry Commoner, critiqued technological progress and argued for post-growth, more sustainable ways of living. Schumacher’s book Small Is Beautiful, which promoted a “maximum of well-being with a minimum of consumption,” was another bestseller. Carter invited him to the White House.

The capstone was The Limits to Growth, published in 1972. Peppered with computer-generated graphs and written in clear, dispassionate language by a team of Massachusetts Institute of Technology graduate students led by two young scholars, Dennis and Donella Meadows, this landmark report delivered a devastating conclusion:

“If the present growth trends in world population, industrialization, pollution, food production, and resource depletion continue unchanged, the limits to growth on this planet will be reached sometime within the next one hundred years. The most probable result will be a rather sudden and uncontrollable decline in both population and industrial capacity.”

The study was initiated and funded by the Club of Rome, an ad hoc, apolitical group of scientists, academics, civil servants, and businesspeople. The Club’s mission was to “rebel against the suicidal ignorance of the human condition.” It sought to better understand the links between economics, the environment, and many other social and political conditions – what it called the ‘world problematique’.

The Limits to Growth was based on a computer simulation called World3, a ‘systems dynamics’ model based on the work of MIT professor Jay Forrester, which tracked the interactions between five factors: population, food production, industrial production, the consumption of nonrenewable resources, and pollution. By linking the world economy with the environment, it was the first integrated global model. The Limits to Growth would put quantitative scenario analysis – possible futures based on hard numbers – into environmental studies.

Whatever its advanced methodology, the report’s message was one that many people could see around them, in pollution, rising prices, plastic-tasting food, urban decline, and political unrest. The Limits to Growth appeared to confirm the sense of being on a civilizational road to some kind of collapse – unless we changed course.

Few people remember that The Limits to Growth was built around a series of scenarios – twelve possible futures stretching from 1972 to 2100. Its main conclusion was that delays in global decision-making would cause the human economy to overshoot planetary limits before growth in humanity’s ecological footprint could be slowed down. The Limits to Growth was then really a warning – about delay, denial, and about committing ourselves to a collective death.

It was also a major hit. The study sold 12 million copies, was translated into thirty-seven languages, and remains the best-selling environmental book of all time. It made headlines in newspapers for months. President Carter and Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau launched similar studies. Carter even invoked it in his inauguration speech in 1977: “We have learned that ‘more’ is not necessarily ‘better,’ that even our great Nation has its recognized limits, and that we can neither answer all questions nor solve all problems.”

There had to be a serious fightback against this rising, and increasingly critical, environmental consciousness, and there was – as we’ll discuss in the next post.

Come With Me If You Want To Live: The Future as Foretold in Classic Sci-Fi Films, is out now from Lexington Books. You can read more about it here.

“All you have to do is cooperate”: V For Vendetta and the vengeful authoritarian regimes to come under collapse

Here’s an excerpt from one of the chapters in my new book, about why conservatism has become so focused on revenge and retribution.

Donald Trump’s (entirely predictable and predicted) victory in the first Republican Party primary – the caucus in conservative evangelical ‘Christian’ dominated Iowa – prompts me to share an excerpt from one of the chapters in my new book.

The book as whole is about how classic science fiction (really, speculative social futures) has in many ways predicted our increasingly dystopian present. Each chapter focuses on a classic sci-fi film, among them Blade Runner, Terminator 2, 12 Monkeys, Brazil, Soylent Green, and the Back to the Future series; these films are used to consider our likely environmental, technological, and political future.

Trumps’s openly – boastfully – vengeful agenda if he retakes power (“I am your retribution”) is frightening, and it’s meant to be. But what has created and spurred on this (certainly unconstitutional) turn in conservative politics? That’s what this particular chapter of the book discusses.

Excerpt: “All you have to do is cooperate”: V For Vendetta and the vengeful authoritarian regimes to come under collapse (chapter 7)

One of the complacent assumptions on the left is that, in wanting to build a better, even a ‘new’ society, the left is much more future-oriented than the right. But the right’s politics far more effectively exploit the scarcity and social conflict driven by early collapse. And they should, because they created them. Depictions of apocalypse distract from the long emergency – of ongoing failing systems, environmental, economic, social, and political crises – one we’re going to have to face, and are already in. More likely than irradiated wastelands, collapse reveals the truth of right-wing politics: hollowed-out states that are unable to provide for or protect people in crises, replacing this weakness with cult leader authoritarianism – as V For Vendetta (2005) starkly dramatizes.

If Nineteen Eighty-Four can be taken as a critique of Soviet totalitarianism, V For Vendetta is clearly about conservative totalitarianism. It’s not really futuristic at all, but backwards-facing. Future-promising neoliberalism turned out to be nothing of the sort. This chapter is about the right’s endgame – what it is, how they’ll seize power, and how they’ll hold onto it. Such regimes thrive on chaos. They might even engineer it.

Conservatism has changed before our eyes. At first, it tried to sell a modernized future, better than the one offered by liberals or the left. It’s not selling utopia anymore, not even a positive vision of the future, only survival against threats and ‘the other.’ The reason is the world it’s created. As Max Haiven, author of Revenge Capitalism (2020), says: “Authoritarianism today does not force society into a formation to fulfil perverse dreams of utopian potential. Rather, it offers austerity, purification and revanchism as means of survival in an ever more hostile world.”

As Dmitry Orlov, the Russian-American engineer and writer on collapse, argues in books such as Reinventing Collapse (2008) and The Five Stages of Collapse (2013), the United States and other countries are likely to face a Soviet style degeneration – a collapse in faith in business as usual, market-based provision, political and social institutions, and ultimately social trust and kindness. This is due to the over-use of natural resources, soaring debt, corruption, and military over-spending. Orlov also emphasizes the personal experience of collapse, and how those who assume they’ll be comfortable and secure will also be humbled.

We’re already experiencing what in hindsight we’ll recognize as an Eastern Europe style collapse, but the capitalist equivalent – a slide into ‘slow dystopia,’ as the graphic novelist, artist, and filmmaker Sarnath Banerjee calls it. And we’re most likely to end up with regimes like that in V For Vendetta. After all, ‘apocalypse’ means revelation, an uncovering of the truth. More likely than irradiated wastelands, collapse reveals the truth of rightwing politics: as a result of neoliberalism, hollowed-out states that are unable to provide for or protect people in crises, replacing this weakness with cult leader authoritarianism.

As we discussed in chapter 1, cyberpunk persists because it increasingly describes our present. As its name suggests, it tends to focus on, and heroize, the marginalized, the hustlers, the subversives – the people the megacorporations (having replaced the state) largely ignore. But anyone secretly hoping for a ‘cool cyberpunk future’ is going to be sorely disappointed. As in V For Vendetta, fascist states that seize power don’t ignore those who are ‘different,’ anyone who isn’t white, middle class, supposedly Christian, and heterosexual. Instead, they persecute them. And anyone who manages to survive, let alone challenge the regime, is going to be severely traumatized, as we’ll see.

Moreover, fascism not only uses fear, it’s also deeply fear based itself, and the reason conservatism can mutate into fascism is that fear has long been central to its ideology, lurking like a dormant strain that can always come back to life, given the right conditions.

As with the crises we’re going to face, the answers lie in the past. Historically, conservatism has long been catastrophe minded: its concern with ‘civilizational collapse’ because of the perceived decline in values, the revolution in sexual freedoms, the supposed decline of the family, the rise of feminism (and the supposed ‘feminization’ of men), immigration bringing different ‘cultures’, and ultimately the ‘decline of the West.’

But there’s also an internal fear, a genuine one for some conservatives, seemingly – about enemies, threats, conspiracies, and their secret plans and agendas. The right has always had a tendency to view the left in paranoid terms, reflecting its fear of social disorder, and ultimately its fear of the masses – from communism, the ‘red menace,’ ‘anarchy,’ new social movements, ‘cultural Marxism,’ community organizing (yes, really), and conspiracies relating to changing demographics. This is because conservatives fear becoming a minority – marginalized, persecuted, even eradicated. As a result, at times (one of them being now), the right sees any victories for the liberal/left as potentially apocalyptic. As this fear has become increasingly mainstream on the right, so has the view that no quarter can be given, that every battle is existential, and relatedly, that voting and political participation need to be curtailed.

Conservatism has always had a self-proclaimed attachment to ‘law and order,’ but combined with paranoia this starts to take on a different, much darker hue – a rationale for pre-emptively stopping ‘them’ before they’re able to introduce their dangerous, freedom-destroying programs. It’s propaganda and projection, but when you think your enemies are this dangerous, it’s only a few steps to justifying their elimination…

Come With Me If You Want To Live: The Future as Foretold in Classic Sci-Fi Films, is out now from Lexington Books. You can read more about it here.

The futures today’s tech billionaires really want

Why to some, dystopian sci-fi is not a warning but a promise.

Here’s an interesting article I missed just before Christmas: ‘Tech Billionaires Need to Stop Trying to Make the Science Fiction They Grew Up on Real.’

Charles Stross’s piece in Scientific American argued that today’s Silicon Valley billionaires grew up reading classic science fiction – but now they’re fixated on trying to make it come true. The problem is not just whether any of this is possible, desirable, or where we should really be putting our efforts (colonies on Mars! Living in giant orbital space stations! Immortality!). To Stross, the real problem is that it embodies a dangerous political outlook.

Stross is a science fiction author himself, a multiple Hugo Award winner whose books include Accelerando and Halting State. But he sounds self-effacing about sci-fi: it’s not a branch of science that advances by experimental inquiry, but a form of popular entertainment that (typically) seeks a bigger audience by selling ideas.

Nonetheless, as he notes, science fiction is also a “profoundly ideological genre – it’s about much more than new gadgets or inventions.” Technologies (real or imagined), and the societies in which they are embedded, are inescapably political. They suggest priorities – which problems matter and which don’t, who makes decisions and who doesn’t, and who can afford them and who can’t.

And to Stross (and others), much of the sci-fi that by their own admission has inspired quite a few tech billionaires has some very worrying foundations – in anything-goes capitalism, technology treated as a quasi-religion, racism and colonialism, eugenics, and even fascism.

As Stross notes, it’s not that every sci-fi creator has a political agenda, rather that, as in any genre, there can be quite a lot of small ‘c’ conservatism, not to say copying, that transmits ideas down generations. Despite this, or because of it, “it leaves us facing a future we were all warned about, courtesy of dystopian novels mistaken for instruction manuals.”

‘Mistaken’, though? As I suggest in my new book, the dystopianism is exactly why these billionaires like the look of some of these futures. It’s not because they’ve forgotten the (often glaringly apparent) lessons of much dark future sci-fi. To the billionaires, these are not warnings but promises.

Of course Elon Musk et al. dream of a cyberpunk future – a world of untrammeled corporate power, private police forces and legal systems, and amazing technologies that are the playthings of the uber-rich (including ‘life extension’). Of course they welcome – or regard as normal, unremarkable, ‘natural’ – these futures of unremittingly gross inequality. And of course they regard these futures as achievable, even inevitable (ironically, at the same time they often bemoan socially-critical sci-fi as being ‘too pessimistic’).

But their futures don’t have to be ours, even if some aspects of the future might be unavoidable. Science fiction can indeed act as a guide – but not a guidebook.

Come With Me If You Want To Live: The Future as Foretold in Classic Sci-Fi Films, is out now from Lexington Books. You can read more about it here.

Why Soylent Green and the serious sci-fi of the 1970s predicted social collapse

Here’s an excerpt from (chapter 4 of) my new book on how classic science fiction films predicted the future we’re increasingly living in.

Here’s an excerpt from (chapter 4 of) my new book on how classic science fiction films predicted the future we’re increasingly living in.

“They’re Running Out of the Damn Green Again!”: Why Soylent Green and the Serious Sci-Fi of the 1970s Predicted Social Collapse

Soylent Green (1973) is the motherlode of 1970s moviemaking, encompassing dystopian sci-fi, environmentalism, urban malaise, social unrest, political corruption, and dark conspiracy. The 1970s saw a series of socially critical, and sometimes dystopian, science fiction films. Soylent Green’s setting reflected a growing environmental consciousness over the previous decade, from Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, to a raft of new environmental regulations and the first Earth Day in 1970. Crucially, these concerns were shared by conservatives. But then a divide began to develop, between the new left’s adoption of a critical environmental conscious that pointed to the destructiveness of industrial capitalism, and the emerging new right that identified the threat from this consciousness and fought back fiercely. Like the shocking truth revealed in the famous ending of Soylent Green, the truth of industrial civilization was too uncomfortable to face.

“How Did We Come to This?”

It begins with a montage of archive photographs, charming scenes of people enjoying nature, accompanied by a slow waltz. Then there’s industrialization, a sense of optimism and progress, the music speeding up. The population grows rapidly, smokestacks, cars rolling off production lines, urban crowds, affluence, and consumption. Followed by pollution, overcrowding, war, famine, disease, the screen splitting into multiple images at once, the music now frenetic. Finally, the music slows down, over wastelands, destroyed forests, barren industrial sites, ending on a thickly polluted New York cityscape. It’s the story of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first century – all in two minutes.

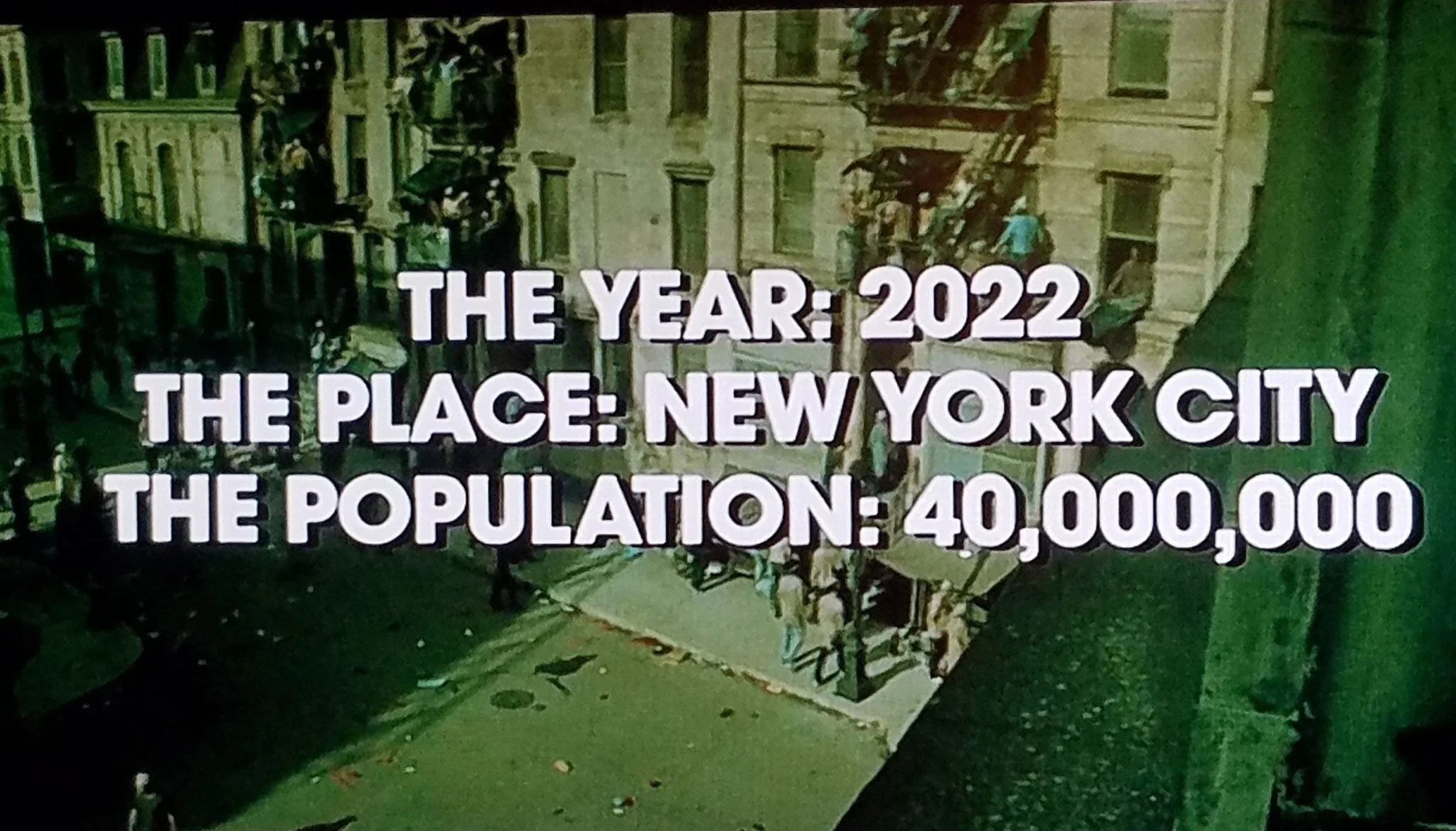

The opening titles by Charles Braverman are among the best ever made in establishing the context for the film – a dirty, broken future – and how we got here. Soylent Green is an early 1970s ecological dystopian detective conspiracy thriller (there’s a combination), directed by Richard Fleischer and starring Charlton Heston, Leigh Taylor-Young, and Edward G. Robinson. It’s loosely based on the 1966 novel Make Room! Make Room! by Harry Harrison, who wasn’t at all happy with the substantial changes made to his story by screenwriter Stanley R. Greenberg. But what was kept was a dystopian future of dying oceans, year-round humidity due to the greenhouse effect, over-population, pollution, poverty, and depleted resources (Richard H. Kline’s photography uses hazy green filters to vividly evoke a poisoned atmosphere). Welcome to 2022.

Soylent Green wasn’t the only one. The 1970s saw a series of socially critical, and sometimes dystopian, science fiction films, many of which seemed to share a sense of urgent alarm about the future we were heading towards. What was going on?

To the author, architect, and academic Douglas Murphy (Last Futures: Nature, Technology, and the End of Architecture), what happened in the 1960s and 1970s was possibly the last chance we had of creating a decent and environmentally sustainable society. The radical movements that developed in these decades – the writer Kirkpatrick Sale called them the “awakened generation” – believed that other futures and new ways of living were possible, even inevitable.

But Murphy also emphasizes that this was a generation that had a strong sense of disaster. In the late 1960s the world was faced with impending doom: it was the height of the Cold War, the coming end of oil (it was thought), and the seemingly irreversible decline of great cities around the world. Out of these crises came a new generation that hoped to build a better future, influenced by visions of geodesic domes, walkable cities, and a meaningful connection with nature. Scenarios of doom and gloom were accompanied by radical but serious ideas to solve the problems we faced (most of which would be largely unrealized futures, it would turn out). This is the story of this chapter – of this era’s most interesting sci-fi movies, the analyses that inspired them, and the warnings that we needed to change course before it was too late.

“How Could I... How Could I Ever Imagine...?”

There had been a handful of eco-disaster films before Soylent Green, mainly monster movies, but none were as relevant or urgent as Fleischer’s film, and none presented so bleak a picture of the human misery that could result from over-population, global warming, and food and energy shortages (this is a film made in the early 1970s that includes climate change, so we really, really can’t say we weren’t warned).

But it wasn’t alone. More serious, thought-provoking science fiction films were released in the 1970s than in the forty years before, and arguably ever since. Soylent Green was just one of a slew of American sci-fi films in the 1970s that, more than imagining the future, reflected the present and its problems, which is of course what sci-fi can be so good at doing. Among them were Colossus: The Forbin Project (1970), The Omega Man (1971), THX-1138 (1971), The Andromeda Strain (1971), Silent Running (1972), Westworld (1973), Zardoz (1973), Rollerball (1975), A Boy and His Dog (1975), The Stepford Wives (1975), Logan’s Run (1976), The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976), Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978), Quintet (1979), and Alien (1979) (we’ll discuss Colossus and Rollerball in later chapters).

The so-called ‘new Hollywood’ took advantage of sci-fi, among other genres, to tell different stories, address social issues of the time, and explore new perspectives. Younger American filmmakers also responded to storytelling and stylistic developments in European cinema, notably the French New Wave, treating their films as cinematic statements and social commentary, reflecting their artistic vision and broader worldview.

Not everyone enjoyed this output, however. Only a few of these films were commercially successful. And some commentators bemoaned the inward turn in science fiction film to America’s increasing social and political problems. For example, writing in 1978, Joan F. Dean complained “all that the science fiction films of the early seventies offer in the way of [traditional sci-fi staple] extra-terrestrial life were bacteria, David Bowie, an invisible civilization, and a few perverts.” Dean dismissively regarded the era as witnessing a dearth of futuristic films, but we remember it now as a particularly rich period of social seriousness in mainstream sci-fi, in large part because of what was going on here at home…

Come With Me If You Want To Live: The Future as Foretold in Classic Sci-Fi Films, is out now from Lexington Books. You can read more about it here.

The future has arrived, pretty much on schedule

Now we’re in the future… how’s it going?

Here’s a list of the classic sci-fi films I focus on in my book, and the (primary) places and years in which they’re set:

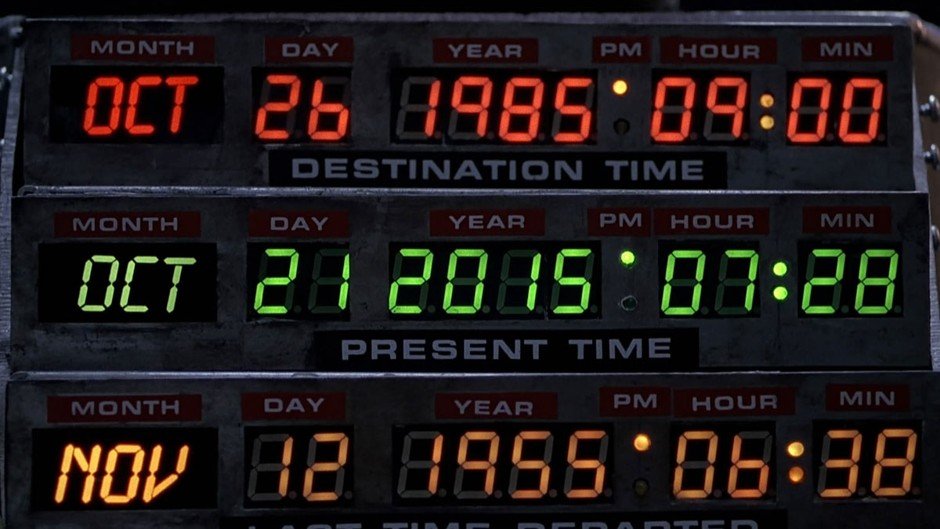

Back to the Future Part II – Hill Valley, 1955 / 1985 (both a and b versions) / 2015

Terminator 2: Judgment Day – Los Angeles, 1995 / 2029

Rollerball – Houston, 2018

Blade Runner – Los Angeles, 2019

Soylent Green – New York City, 2022

V For Vendetta – England, 2028

12 Monkeys – Philadelphia and Baltimore, 2035 (and 1990, 1996, World War I…)

Brazil – Britain, “Somewhere in the 20th Century”

Colossus: The Forbin Project – Colorado, year unspecified but the original book is set in the 1990s

Which is to say, we’re now living in (or have lived through, in some cases) some of the years depicted in these films. So how successful were they in predicting our future (present)?

When we ask this question, we might think first about the technologies they did or didn’t anticipate. Indeed, the fact that our future-present doesn’t include flying cars has been used by some so-called accelerationists to argue for a more ‘pro-technology’ (really meaning, deregulatory) approach to deliver the ‘future we were promised’ by sci-fi.

This focus on technology is understandable (it is science fiction, after all), but it also distracts us from what the more socially serious, critical sci-fi I focus on in the book was really about, namely the environmental, social, and political futures we were heading towards, and now where we’ve nearly arrived. Sci-fi dystopias are usually comfortably decades in the future. Until suddenly, they’re not.

Perhaps then the more important question I discuss in the book is why our fictional depictions of the future largely haven’t changed ever since some of these landmark films were released – why, in the most important respects, have they been proved essentially correct? To this, my answer is that these fictional futures persist, especially cyberpunk themed, environmentally depleted, corporate dominated, grossly unequal dystopias, because the conceivable future hasn’t changed. This is why films such as Blade Runner haven’t really dated – because we didn’t change course from the future(s) they depicted.

But why then didn’t we listen to their warnings?

In the 2015 movie Tomorrowland (named after the once-futuristic land in Disney theme parks), the character played by Hugh Laurie, the governor of a once fantastical city which is now in a state of decay, laments the failure of his plan to prevent a catastrophic future by projecting images of disaster to humanity as a warning. Instead, as he notes, “They didn’t fear their demise, they repackaged it. It can be enjoyed as video games, as TV shows, books, movies. The entire world wholeheartedly embraced the apocalypse and sprinted towards it with gleeful abandon.”

Perhaps this is part of it, and some critics and commentators have certainly blamed dystopian fiction for today’s widespread pessimism about the future (at least in many Western nations). And yet, it’s not the job of creators of popular culture to promote positive visions of the future absent the factors that could help to make these visions come true. The only ‘responsibility’ of creators is to tell the truth, at least how they see it – that, for example, the climate emergency, long predicted by often-derided and dismissed environmental ‘doomists’ since the 1970s, has surely, undeniably now begun.

It’s not then a failing of creators’ imaginations (let alone a conspiracy of despair) that we’re stuck in dystopian visions of the future, it’s that politically, economically, and socially we’ve essentially been stuck on the same trajectory towards futures that are decidedly dystopian. Moreover, the fears expressed in some 1970s sci-fi have turned from predictions into descriptions - not because we heeded their concerns, but because we didn’t. This is the world that sci-fi ‘promised’ us, not a future of flying cars.

So, welcome to 2024!

Come With Me If You Want To Live: The Future as Foretold in Classic Sci-Fi Films, is out now from Lexington Books. You can read more about it here.

If classic sci-fi has predicted it, is the future still unknown?

At the end of Terminator 2, we’re travelling down a highway at night, again. Sarah Connor says, “The unknown future rolls towards us. I face it for the first time with a sense of hope.” But can we do the same?

Here’s the afterword from my new book, about how classic science fiction has in many ways predicted the future we’re now increasingly living in:

At the end of Terminator 2, we’re travelling down a highway at night, again. Sarah says, “The unknown future rolls towards us. I face it for the first time with a sense of hope. Because if a machine, a Terminator, can learn the value of human life, maybe we can too.”

As Jonathan Lear writes in Radical Hope (2006), “What makes… hope radical is that it is directed toward a future goodness that transcends [our] current ability to understand what [that] is.” In every moment, there are always routes to different futures.

Terminator 2 originally ended even more optimistically. We’re in a playground again, but thirty years in the future (in other words, just about now). Sarah watches children playing, including an adult John playing with his own daughter:

“August 29, 1997, came and went. Nothing much happened. …People went to work as they always do. Laughed, complained, watched TV, made love. I wanted to run to through the street yelling to grab them all and say, “Every day from this day on is a gift. Use it well.” Instead, I got drunk. …But the dark future which never came still exists for me. And it always will, like the traces of a dream. John fights the war differently than it was foretold. Here, on the battlefield of the Senate, his weapons were common sense and hope. The luxury of hope was given me by the Terminator. Because if a machine can learn the value of human life, maybe we can too.”

In contrast to some of the other films we’ve discussed, it was the studio that wanted a more ambiguous ending. Mario Kassar, the lead producer, felt it was too neat, too positive compared to the dark tone of the rest of the story, as if it came from a different film (a more open ending, implying that the struggle for the future is an ongoing one, would also more easily allow for sequels). Test audiences agreed, and James Cameron relented.

This book has been less about how dystopias have warned us about some distant, possible future, and more what they’ve told us about the fast-oncoming, increasingly probable present. Since we’re here now, it might be time to move on from fictional dystopias. Obviously, good sci-fi continues to be produced, and consumed, as it should. But, we might ask, what do they really tell us that we don’t already know – about ecological catastrophe, class exploitation, and technological hubris? Just as the films highlighted here predicted, the future is becoming less unknown. Paradoxically, ‘no fate but that we make is right’ is correct – but only if we first accept the reality of the world, and of the world soon to come.

This doesn’t mean it’s over. There might be no future emergency for which we must prepare. Dystopia is here already for some people – it has been for a long time – and for more of us soon. Magical technologies won’t save us, nor will charismatic leaders touting simplistic solutions. But creativity, communities, and commitment will help to save some of us, in some times and places. Just how many times and places, and how many people, is still up to us.

And while much of the argument here has been about inevitability, about the unavoidability of crisis and collapse, there are also better things we can’t anticipate, maybe can’t even begin to imagine. There are the things we don’t yet know – ideas, organizations, movements, ways of living and working and more – in the minds and hearts of new generations who are growing up in collapse and (yet) still want to build better, safer, fairer futures.

In Terminator: Dark Fate, Grace (Mackenzie Davis), a human augmented future super soldier, grabs Sarah’s phone to figure out the geographical coordinates of an anonymous text message sent to the device. “What are you doing?”, asks Sarah. Not wanting to waste time trying to explain her advanced knowledge, Grace responds, “Future shit.”

Come With Me If You Want To Live: The Future as Foretold in Classic Sci-Fi Films, is out now from Lexington Books. You can read more about it here.

Preface: “Now Read on… into the Fantastic World of the Future!”

Here’s the preface to my new book, Come With Me If You Want to Live: The Future as Foretold in Classic Sci-Fi Films.

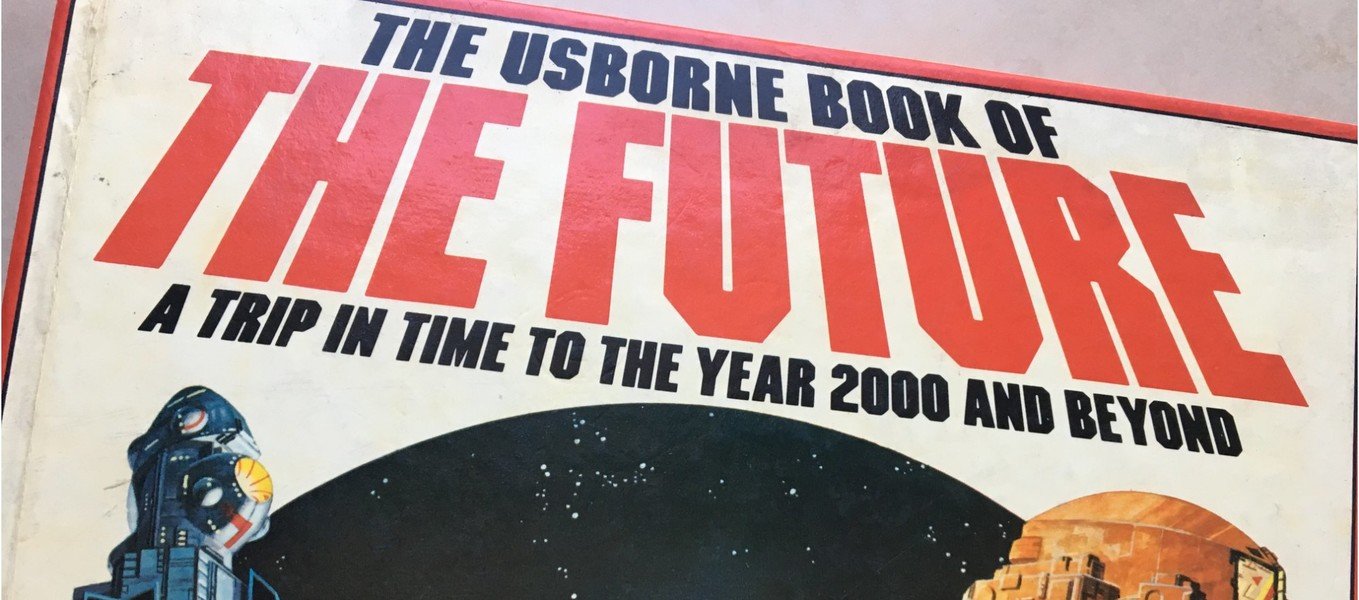

That’s how each of the three sections (Robots, Future Cities, Star Travel!) of The Usborne Book of the Future begin. Written by Kenneth Gatland and David Jefferis, it was published in 1979, and it was one of my favorite books when I was growing up (some page spreads from the book are featured in this post).

Nothing dates faster than the future. And you can certainly play that game with The Book of the Future, subtitled A Trip in Time to the Year 2000 and Beyond. So no, our houses don’t yet have automated servants handing out trays of drinks, and there aren’t robot forest firefighters. Or everyday Space Shuttle flights, space elevators, factories in Earth orbit, or massive domed cities, let alone an Olympics on the Moon (anticipated for 2020). Many of the timescales for supposed technologies-to-come are way off, if they happen at all, although maybe one day we will inhabit cities in space (indeed, some of today’s big tech billionaires seem to be counting on it).

But what I realize now is that, even though it was a book for children and some of its predictions didn’t come to pass, in other respects the future was contained in its pages, and I had seen it all the way back then.

As The Book of the Future foresaw, we do carry minicomputers in our pockets, much more powerful than the ‘risto’ watches it featured, and our homes are full of networked gadgets. Robots have “increasingly take[n] over the jobs of skilled engineers in factories.” Artificial intelligence is advancing into our lives. Shopping is increasingly online (The Book of the Future confidently predicted that TVs will be “used to order shopping via a computerized shopping center a few kilometers away”). Electric vehicles will eventually become widespread (the book predicted an “almost totally electric world”). Computerized weapons systems are shaping the future of war. “Electronic conferencing” is finally common (prompted by the pandemic, not merely because of presumed “convenience”). And some people are experimenting with sea-borne living, akin to the floating pyramid cities featured in the book.

That it got at least some of these predictions largely right isn’t surprising. The Book of the Future was based on the research of scientists and organizations including Bell Aerospace, Boeing, and NASA, alongside Arthur C. Clarke and Omni magazine (co-author Kenneth Gatland was also a leading spaceflight theorist). But there were other things about the possible future that the book spent much less time discussing – with one important exception.

I was born in 1971. The generation before me, some of them at least, could still be excited about the future. As in The Book of the Future, they could plausibly believe they might one day become space tourists, as well as find ways to eliminate poverty, crime, war, and disease here on Earth. A generation later, as a child I still read comics about daring space adventurers, but I knew they had a decidedly retro, 1950s feel to them. They were yesterday’s future, not the actual future.

This was because, as I grew up, the actual future seemed to get darker, it was darker: the possibility of nuclear annihilation in the Second Cold War, demonstrations, strikes, mass unemployment, increasing inequality, and the growing sense, as the punk movement put it, of ‘no future.’

As we’ll see, this was reflected – and predicted – in fiction as well. From the late 1960s onwards, there was a new adultness in science fiction, including at the movies. Technical advances in filmmaking helped, but the real progress was in the subject matter: there was much less fantasy about aliens, and much more fatalism about humanity and its future (or possible lack of it).

Today, young people may be even more anxious about what’s to come. Unfortunately, it’s probably worse than most of them imagine. In their future, they could see civilization – at least in its present, somewhat predictable form – collapse, due to everything from climate change to wars over dwindling resources. In some of its most fundamental warnings, the more adult, dystopian sci-fi of the 1970s is fast turning into fact. This is partly what this book is about.

To understand what happened to the future, we have to go back to when I was young, to a point when two very different futures were still possible and the choice between them was being made. In between its easy-to-mock certainty about coming Lunar Olympics and interstellar starships, it was this critical choice that The Book of the Future really got right. What really strikes me looking back at (and at the time, as I remember), is its double-page spread titled “Two trips to the 21st century”, and the stark contrast it presents between a “Garden city on a cared-for planet” and a “Polluted city of a dying world.”

In the latter, there’s over-population, vehicles trundle along still powered by gasoline (alternative energies were not pursued), the environment is dying (fake plastic trees line the roads), the air is a chokingly thick brown-orange (pedestrians wear gas masks), the brutalist urban infrastructure is decaying, and people are out of work and under-fed. But in the former, fumeless hydrogen and electric powered vehicles glide through a refurbished, greenified city, beneath monorails and alongside walking and cycling lanes. The air is fresh spring blue, the plants and trees are vibrant green.

There were two possible futures back then, it said, one darkly dystopian, the other much brighter – not a whizzy 1950s Jetsons-style techno-utopia, but still a pretty good one.

What I know now, and we’ll discuss in this book, is that these two possible futures were based on predictions set out in landmark publications like The Limits to Growth, published just a few years before in 1972. And we’ll examine how, contrary to their fierce critics at the time, the predictions made in these publications are increasingly coming true.

We didn’t heed these warnings, or those depicted in popular culture pretty much ever since. Fundamentally, this book is about why. The short answer is that, starting in the 1970s, an organized and well-funded campaign was mounted against recognizing, let alone doing anything serious about, the threats we faced, and it largely succeeded in persuading people that the future would effectively take care of itself.

Indeed, we’ll see how it was these predictions, both in fiction and non-fiction, of a dark future that helped to propel – in some ways helped to create – a new political movement, which until the 1970s had been relatively marginalized. What’s been neglected in many previous histories is how this movement’s attractive promises – that there were no limits to growth, and that technology would solve the major problems we face – were crucial in bringing them, and a new type of politician, to power. And so we set off towards one of the two futures depicted in my children’s book – the wrong one.

We can’t say we weren’t warned, including by some of the best science fiction films of the past fifty years, which we’ll use here to discuss what’s going to happen next. We’ll also uncover the sometimes surprising yet hidden-in-plain-sight meanings of these films – meanings that are, however else some of these films might seem dated, now more relevant than ever (inevitably, there are major spoilers for the films).

Of course, the films represent a personal collection of favorites, and, I hope, a pretty good selection based on their predictive power, for their ability to foresee the future. They’re also a way of telling the story presented here, of how we lost the future, or rather how it was taken from us. Indeed, at times they become part of the story; in some cases their warnings were (and still are) dismissed as alarmist, even part of a progressive ‘plot’ to end progress and immiserate millions. Obviously, their inclusion here is intended to indicate that they got more fundamentally right than wrong.

It’s not the future their creators wanted then, or we want now (most of us, anyway). But the more we understand what’s coming, the more we might be able to prepare for it.

So, read on, not into the fantastic, but definitely into the dramatic, world of the future.

Come With Me If You Want To Live: The Future as Foretold in Classic Sci-Fi Films, is out in November from Lexington Books. You can read more about it here.

It’s too late to avoid Terminator 2, but there’s still time for a human resistance

“Come with me if you want to live”

My forthcoming book discusses the dominance of dystopian visions of the future, which is hardly surprising given the multiple, overlapping environmental, economic, and political crises we face. In the book, I use nine classic sci-fi movies to discuss various aspects of the coming dystopia. The last of them is Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991).

The most obvious way to interpret the Terminator series is as a warning about killer robots, and a necessary one. Warfare is being automated, and robots are creeping into policing. Big tech is working, often secretly, with states on defense and intelligence systems. Then there’s pervasive surveillance.

But as Maxim Pozdorovkin, director of the documentary The Truth About Killer Robots, says: “This idea of a single, malevolent AI being that can harm us, the Terminator trope …it’s created a tremendous blind spot. [It gets us] thinking about something that we’re heading towards in the future, something that will one day hurt us. If you look at the effects of automation broadly, globally, right now, it’s much more pervasive. The things happening – de-skilling, the loss of human dignity associated with traditional labor – they will have a devastating effect much sooner than that long-distance threat of unchecked AI.”

So as I discuss in the book, Terminator 2 is really about technology done to us, rather than under our control – through automation, algorithms, surveillance, disinformation, and manipulation. But this also means it’s something that is actually under human control; it’s to do with corporate and state power, a lack of regulation, and democratic deliberation.

Not bad for an action movie with some of the best stunts ever filmed.

But for more on that, you’ll have to read the book.

Come With Me If You Want To Live: The Future as Foretold in Classic Sci-Fi Films, is out in November from Lexington Books. You can read more about it here.

How Brazil dashes the hopes for a luxury, leisure-filled future communism

“Bloody paperwork”

My forthcoming book discusses the dominance of dystopian visions of the future, which is hardly surprising given the multiple, overlapping environmental, economic, and political crises we face. In the book, I use nine classic sci-fi movies to discuss various aspects of the coming dystopia. One of them is Brazil (1985).

If you’ve seen it, it’s impossible to think about the film without its theme song entering your head. But Brazil doesn’t take place there. Rather, it’s named after its recurring theme Aquarela do Brasil (Watercolor of Brazil), written by Ary Barroso and known as just ‘Brazil’ to Western audiences. But while its use seems nonsensical at first, especially in a dystopian story, it makes sense the more you think about it.

Although not a hit initially, Brasil has become one of the 20 most recorded songs of all time. It’s fun, joyful, expressive, infectious, and absurd. Barroso wrote the song while he was stuck inside his house during a thunderstorm. It’s a dream of escape – one day.

Unfortunately, there will be no escape in director Terry Gilliam’s dystopian masterpiece. We’re in a run-down, polluted, consumerist, hyper-bureaucratic totalitarian future Britain (again), “Somewhere in the 20th century” we’re told by the title card. Gilliam says Brazil isn’t science fiction, more of a “documentary” or “political cartoon” of the world we already live in.

But really, its totalitarian setting and descent into darkness suggests how a system that’s supposed to provide for our wants and needs spirals out of control, how institutions become our oppressors, how we’re in collective denial about collapse, but how some people continue to dream of a more human society – one day.

In the book, I use Brazil to discuss how, despite its attractiveness, the recent resurgence of interest in left ‘accelerationism’ or automated communism – that we could use new technologies to finally realize the perfectly fair, planned economy – not only ignores the very real environmental collapse we’re heading towards, it also has worrying implications for democracy.

This is where, well before its time, Brazil depicts a society overrun by centralized bureaucracy where nothing really works as it should, but the system can never, ever admit it.

But for more on that, you’ll have to read the book.

Come With Me If You Want To Live: The Future as Foretold in Classic Sci-Fi Films, is out in November from Lexington Books. You can read more about it here.

V For Vendetta and the vengeful authoritarian regimes to come under collapse

“All you have to do is cooperate”: V For Vendetta and the vengeful authoritarian regimes to come under collapse

My forthcoming book discusses the dominance of dystopian visions of the future, which is hardly surprising given the multiple, overlapping environmental, economic, and political crises we face. In the book, I use nine classic sci-fi movies to discuss various aspects of the coming dystopia. One of them is V for Vendetta (2006).

Welcome to the England of 2028. America has been fractured by what sounds like a second civil war. A pandemic, the St. Mary’s Virus, has ravaged the planet. High Chancellor Adam Sutler (John Hurt) leads a white supremacist, theocratic police state controlled by the Norsefire party, a successor to the Conservative party. Disease and war enabled it to seize power.

So too in our most likely future: authoritarians will use fear and insecurity to promise order at the cost of freedom.

One of the complacent assumptions on the left is that, in wanting to build a better, even a ‘new’ society, the left is much more future-oriented than the right. But as I discuss in the book, the right’s politics far more effectively exploit the scarcity and social conflict driven by early collapse (and they should do, because they created them). As Chancellor Sutler says, “I want this country to realize that we stand on the edge of oblivion. I want every man, woman and child to understand how close we are to chaos. I want everyone to remember why they need us!”

Depictions of apocalypse, however dramatically interesting, actually distract us from the ‘long emergency’ – of ongoing failing systems, environmental, economic, social, and political crises – one we’re going to have to face, and are already in. More likely than irradiated wastelands, collapse reveals the truth of right-wing politics: hollowed-out states that are unable to provide for or protect people in crises, replacing this weakness with cult leader authoritarianism – as V For Vendetta starkly dramatizes.

This suggests the truth about the right’s endgame – what it is, how they’ll seize power, and how they’ll hold onto it. Such regimes thrive on chaos. They might even engineer it.

But for more on that, you’ll have to read the book.

Come With Me If You Want To Live: The Future as Foretold in Classic Sci-Fi Films, is out in November from Lexington Books. You can read more about it here.

Why we don’t listen to stories like Colossus that tell us not to trust the machines

“This is the voice of world control”: Why we don’t listen to stories like Colossus that tell us not to trust the machines

My forthcoming book completed discusses the dominance of dystopian visions of the future, which is hardly surprising given the multiple, overlapping environmental, economic, and political crises we face. In the book, I use nine classic sci-fi movies to discuss various aspects of the coming dystopia. One of them is Colossus: The Forbin Project (1970).

Colossus – which deserves to be better known than it is – was tautly but almost naturalistically directed by Joseph Sargent, who also made the classic original version of The Taking of Pelham One Two Three (1974), and based on D.F. (Dennis Feltham) Jones’ 1966 first novel (‘A Novel of Tomorrow that Could Happen Today!’), with a screenplay by James Bridge, who would write and direct another 1970’s classic about dangerous over-confidence in technology, The China Syndrome (1979).

In the story, the US has built a supercomputer that is designed to bring world peace. Of course, that’s not how it turns out...

It’s a genre trope, of course: the seemingly benign but actually malevolent machine that threatens humanity. Normally, we’d say this is about a fear of technological progress, dehumanization, and of systems we create becoming our masters rather than our servants. Colossus certainly touches on these themes, and it’s prescient about our digitally connected age, including technological dependency, and privacy and surveillance.

But as I discuss in the book, it’s also a good metaphor for being trapped inside what we were promised would be a benign economic ‘computer’ – one that its ‘programmers’ confidently told us would bring universal peace and security, but in reality has wrought the opposite.

Neoliberalism claimed that it had discovered a perfect economic machine that could meet every need and solve every problem, one that could also operate on its own – hence the feeling that we’ve lost control, and why we’re anxious and angry about it.

It’s not surprising then, living under the rule of the machines, that we feel like ones and zeros, in a program we can’t rewrite, inside a computer we can’t reboot.

But for more on that, you’ll have to read the book.

Come With Me If You Want To Live: The Future as Foretold in Classic Sci-Fi Films, is out in November from Lexington Books. You can read more about it here.

How the corporate-controlled ‘utopia’ of Rollerball isn’t as content as it first appears

“Your future comfort is assured”: How the corporate-controlled ‘utopia’ of Rollerball isn’t as content as it first appears

My forthcoming book discusses the dominance of dystopian visions of the future, which is hardly surprising given the multiple, overlapping environmental, economic, and political crises we face. In the book, I use nine classic sci-fi movies to discuss various aspects of the coming dystopia. One of them is Rollerball (1975).

It’s 2018. In a business-run future, there is no war, poverty, or unrest on planet Earth – apart from the violence played out in the Rollerdome that is. All material needs are met, and we still get to let off steam by watching our favorite Rollerball team battle their opponents on our behalf in an exciting combination of (American) football, motocross, and gladiatorial combat. Compared to most of the futures discussed in the book, it doesn’t actually sound so bad.

As I discuss in the book, in both fact and fiction the late 1960s and early 1970s saw a rising tide of environmental consciousness, and indeed activism. As parts of this movement became more radical, especially in its criticisms of industrial capitalism, there had to be a serious fightback – and there was.

Corporations and their representative bodies organized to defend the ‘free enterprise system’ and funded new institutions such as think tanks to promote deregulation and other pro-corporate policies. Rollerball depicts the kind of corporate dominated society that would result – seemingly a utopia of limitless consumer choice, but actually a dark age of commodification, violence, and alienation.

In our world, the ‘new’ right’s well-funded campaign effectively pushed the mainstream environmental movement back into conservation efforts and narrow technical issues. As a result, a critical moment was lost – and perhaps our last real chance to change the future.

But for more on that, you’ll have to read the book.

Come With Me If You Want To Live: The Future as Foretold in Classic Sci-Fi Films, is out in November from Lexington Books. You can read more about it here.

How Soylent Green and the serious sci-fi of the 1970s predicted social collapse

“They’re running out of the damn Green again!”: How Soylent Green and the serious sci-fi of the 1970s predicted social collapse

My forthcoming book discusses the dominance of dystopian visions of the future, which is hardly surprising given the multiple, overlapping environmental, economic, and political crises we face. In the book, I use nine classic sci-fi movies to discuss various aspects of the coming dystopia. One of them is Soylent Green (1973).

Soylent Green is an ecological dystopian detective conspiracy thriller (now there’s a combination), directed by Richard Fleischer and starring Charlton Heston, Leigh Taylor-Young and Edward G. Robinson. It presents a dystopian future of dying oceans, year-round humidity due to the greenhouse effect, overpopulation, pollution, poverty, and depleted resources (Richard H. Kline’s photography uses hazy green filters to vividly evoke a poisoned atmosphere). And it’s set in 2022...

The 1970s saw a series of socially critical, and sometimes dystopian, science fiction films, many of which seemed to share a sense of urgent alarm about the future we were heading towards (and now, of course, increasingly where we’ve arrived).

Soylent Green’s setting reflected a growing environmental consciousness over the previous decade, from Rachel Carson’s bestselling book Silent Spring, to a raft of new environmental regulations and the first Earth Day in 1970. Crucially, these concerns were shared by conservatives. But then a divide began to develop, between the new left’s adoption of a critical environmental conscious that pointed to the destructiveness of industrial capitalism, and the emerging new right that identified the threat from this consciousness and fought back fiercely.

Like the shocking truth revealed in the famous ending of Soylent Green, the truth of industrial civilization was too uncomfortable to face.

But to understand how all this played out, in both fact and fiction, you’ll have to read the book.

Come With Me If You Want To Live: The Future as Foretold in Classic Sci-Fi Films, is out in November from Lexington Books. You can read more about it here.

No-one believes the plague-ridden future of 12 Monkeys could actually happen, and then…

“Oh, wouldn’t it be great if I was crazy? Then the world would be okay”: No-one believes the plague-ridden future of 12 Monkeys could actually happen, and then…

My forthcoming book discusses the dominance of dystopian visions of the future, which is hardly surprising given the multiple, overlapping environmental, economic, and political crises we face. In the book, I use nine classic sci-fi movies to discuss various aspects of the coming dystopia. One of them is 12 Monkeys (1995).

With 12 Monkeys, Terry Gilliam directed one of the definitive dystopias of the 1990s, after he did the same with Brazil in the 1980s. The film’s ‘recycled future’ production design echoes the film’s story – how the future is made up of the past, rather than being shiny brand new. If the Back To The Future series (which I also discuss in the book), at least at first appears to offer the possibility of changing the future through the past, 12 Monkeys suggests that this is doomed – that we are prisoners of time.

In a similar way, because we’ve all seen so many (often dark) depictions of the future (and because we already know what might happen), like the main character in 12 Monkeys mentally we’re also effectively living both in our time and the future. Maybe we didn’t believe ourselves, didn’t believe they could become real. And then, of course, they did…

That’s what recurring depictions of dystopia really are, nightmare-memories that have haunted us for a long time. Contrary to techno-optimists then, the dark future is not a self-fulfilling prophecy we could avoid if only we were more positive; it’s a future reality we’ve already foreseen.

As for what exactly we’ve all foreseen, well, for that you’ll have to read the book.

Come With Me If You Want To Live: The Future as Foretold in Classic Sci-Fi Films, is out in November from Lexington Books. You can read more about it here.

How Back To The Future predicts the decline of middle-class security

“I mean, how can all this be happening? It’s like we’re in hell or something”: How a 1980s sci-fi comedy adventure is much smarter than it first appears

My forthcoming book discusses the dominance of dystopian visions of the future, which is hardly surprising given the multiple, overlapping environmental, economic, and political crises we face. In the book, I use nine classic sci-fi movies to discuss various aspects of the coming dystopia. One of them is the Back to the Future series.

This might seem a strange choice – but Back to the Future is especially smart, as well as entertaining, about how the past can lead to a dilapidated, dystopian future.

Arguably, only Back to the Future: Part II is science fiction, although the trilogy as a whole hinges on the genre trope of an advanced new technology, in this case time travel, that becomes a hazard with all sorts of unintended consequences. But that’s just a plot device. Really, all of the films are about utopia and dystopia, not always in the obvious way of films like Blade Runner, but in important ways nonetheless.

When we ask, ‘what happened to the future?’, we might at first think about the near-magical technologies that we (older generations, at least) were seemingly ‘promised’, including flying cars. But there’s something more important underlying these technological visions which also hasn’t happened: a shared increasing prosperity, ever-increasing leisure time facilitated by new technologies, investment in shiny, efficient cities, and a dynamic but organized future.

Most of all, we’re missing the optimism founded in ongoing social progress. It’s the decline of this optimism, among other things, that Back to the Future brilliantly depicts – and even more, that the particular middle-class American promise of utopia may always have been a lie, and its decline has sown the seeds of its coming (and increasingly present) dystopia. But to understand exactly why, you’ll have to read the book!

Come With Me If You Want To Live: The Future as Foretold in Classic Sci-Fi Films, is out in November from Lexington Books. You can read more about it here.

Why we’re stuck in a Blade Runner future that’s forty years old

“I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe”: Why the sci-fi future effectively ended with Blade Runner

My forthcoming book discusses the dominance of dystopian visions of the future, which is hardly surprising given the multiple, overlapping environmental, economic, and political crises we face. In the book, I use nine classic sci-fi movies to discuss various aspects of the coming dystopia, starting with… Blade Runner (1982).

We have to start in Blade Runner, because that’s where today’s visions of the future really started – and as I discuss in the book, effectively ended. There’s a thousand (and many more) analyses of the film, but the obvious fact, hidden in plain sight, is that Blade Runner persists because its future remains our most likely future, and our present.

Blade Runner vividly depicts a future of urban decay and under-investment, over-population, corporate domination, commodification, and alienation. The lack of flying cars in our own time isn’t the point. Described by director Ridley Scott as “Hong Kong on a very bad day”, the film depicts a future Los Angles of soaring inequality, environmental degradation, pollution, urban sprawl, absent government, and (literally) dehumanizing technological progress.

It’s the distillation of all dystopias – the reason it still feels relevant, even if (or perhaps because) it might now be too late to act as a warning. It tells us what it’s always told us, and most importantly, points towards why we didn’t listen, why we didn’t try to change the future it warned us about.

So the more fundamental question, and the central theme of my book, is why we didn’t (and perhaps still don’t) feel we can change these things, which is really a political question – and also the outcome of a particular political project. But for more on that, you’ll have to read the book…

Come With Me If You Want To Live: The Future as Foretold in Classic Sci-Fi Films, is out in November from Lexington Books. You can read more about it here.

The future we were really promised

Blaming creators for their recurringly dark visions of the future gets the problem exactly the wrong way around: we created the future that they reflect in their pessimistic views about what’s to come.

One of the newsletters I subscribe to is James Pethokoukis’ Faster, Please!, described by its author as “about creating a better America and world by accelerating scientific discovery, technological progress, and commercial innovation. (And creating a pro-progress culture.)” James’ politics differs greatly from mine – he’s a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) – but his newsletter is always an interesting, informative, and thoughtful read, and recommended for anyone interested in technology, innovation, and indeed the future.

Like me, James has a book out (mine is published next month), in his case titled The Conservative Futurist: How To Create the Sci-Fi World We Were Promised. It encapsulates what he calls ‘Up Wing’ thinking, namely:

“Up Wing is my shorthand for a solution-oriented future optimism, for the notion that rapid economic growth driven by technological progress can solve big problems and create a better world of more prosperity, opportunity, and flourishing. The most crucial divide for the future of America isn’t left wing versus right wing. It’s Up Wing versus Down Wing.”

That said, it is, as his title suggests, still fundamentally an economically conservative argument (in short, broadly anti-regulation, but pro-government investment in basic science and research). Fair enough. But what I want to question here is James’ (and quite some others’) critique of the role that popular culture might have played in altering our view of the future - for the worse.