The future has arrived (as predicted)

Reviewers love to point out what sci-fi got wrong (‘where’s my flying car?’ etc). But my new book focuses on what many sci-fi films were really warning us about - the dystopian future(s) - and how in these respects they were fundamentally right.

My new book, Come With Me If You Want To Live: The Future as Foretold in Classic Sci-Fi Films, is out in November. It’s a timely one, I think (unfortunately) – about how the future, particularly dystopian futures, have been depicted in science fiction films and why ‘we’ haven’t have taken these visions seriously enough.

Here in the 2020s, we’ve reached the point depicted in many sci-fi films of the past fifty years. Reviewers love to point out what sci-fi stories got wrong (‘where’s my flying car?’ etc). But my book focuses on what many of these films were really warning us about - the dystopian future(s) - and how in these respects they were fundamentally right.

Last year, 2022, was also the fiftieth anniversary of the most important report most people might never heard of, The Limits to Growth. A media sensation at the time for predicting social collapse, it’s still unnervingly prescient about our present and helps to explain what’s happening now.

The book uses blockbuster and cult classic sci-fi films to describe what’s coming next – in politics, economics, technology, the environment, and our day-to-day lives (I’ll briefly introduce the selected films in later blog posts). It shows how the predictions contained in studies such as The Limits to Growth are now coming true (indeed, The Limits to Growth even directly informed some of the films I discuss in the book).

So, we can’t say we weren’t warned, including by some of the best science fiction films of the past fifty years, which I use in the book to discuss what’s going to happen next. I also uncover the sometimes surprising yet hidden-in-plain-sight meanings of these films – meanings that are, however else some of these films might seem dated, now more relevant than ever (inevitably, there are major spoilers for the films, if you haven’t seen them already).

Of course, the films represent a personal collection of favorites, but, I hope, also a pretty good selection based on their predictive power, for their ability to foresee the future. In addition, they’re a way of telling the story presented in the book, of how we lost the future, or rather how it was taken from us.

Indeed, at times they become part of the story itself; in some cases their dramatized warnings were (and still are) dismissed as alarmist, even part of a progressive ‘plot’ to end progress and immiserate millions. Obviously, their inclusion in the book is intended to indicate that they shouldn’t have been dismissed at the time, and neither should they now.

So, the book is really less about how dystopias have warned us about some distant, possible future, and more what they’ve told us (and still can tell us) about the fast-oncoming, increasingly probable present.

Some might say, since we’re here now, it might be time to move on from fictional dystopias. Obviously, good sci-fi continues to be produced, and consumed, as it should. But, we might ask, what do they really tell us that we don’t already know – about ecological catastrophe, class exploitation, and technological hubris? Just as the films included in the book predicted, the future is becoming less unknown.

This doesn’t mean it’s over. There might be no future emergency for which we must prepare. Dystopia is here already for some people – it has been for a long time – and for more of us soon. Magical technologies won’t save us, nor will charismatic leaders touting simplistic solutions. But as I argue in the book, creativity, communities, and commitment will help to save some of us, in some times and places. Just how many times and places, and how many people, is still up to us.

Come With Me If You Want To Live is the history of why we didn’t get the future we were promised, and who is responsible for this – but how we will get the future that was predicted fifty years ago. It’s not the future their creators wanted then, or we want now (most of us, anyway). But the more we understand what’s coming, the more we might be able to prepare for it.

Come With Me If You Want To Live: The Future as Foretold in Classic Sci-Fi Films, is out in November from Lexington Books. You can read more about it here.

Why The Creator is so important to the future of science fiction on film

What the The Creator might mean for the future of serious science fiction on film.

Gareth Edwards’ The Creator, just opened in cinemas, is a notable return from the director of Rogue One: A Star Wars Story and Godzilla (2014). Reviews have ranged from mixed to very positive; critics have generally praised its world building and effects, while suggesting that story-wise it doesn’t do anything new. Even if that’s fair (I think it’s a bit grudging myself, having greatly enjoyed seeing it this weekend), the real importance of the film might be in how it was made and what this could mean for the future of filmmaking, including science fiction.

It's true that The Creator evinces a set of sci-fi tropes (Edwards himself has described the film as “Blade Runner meets Apocalypse Now”). It’s 2070, and the world is split between a United States waging war on artificial intelligence and a ‘New Asia’ where A.I. peacefully co-exists with humans. Ex-special forces agent Joshua (John David Washington) is recruited to hunt down and kill an elusive figure known as Nirmata (Hindi for ‘creator’), the architect of an advanced A.I. that could make a decisive difference in the conflict. Joshua reluctantly journeys into the dark heart of A.I.-occupied territory (the most humanoid of which are called ‘simulants’ in the story), only to discover that the weapon he’s been instructed to destroy is in the form of a young child…

Certainly, you can anticipate some of the key plot developments and even how it all resolves, and there’s a fair critique that the film falls into a familiar cyberpunk-style (and ironically somewhat dehumanizing) ‘techno-Orientalism.’ But appropriately from the director of Rogue One, rather than an exploration of artificial intelligence, really The Creator is an anti-imperial(ism), anti-War (on Terror) story. Edwards has acknowledged that Star Wars’ ‘used future’ aesthetic is amongst its sci-fi inspirations (there’s even a looming, all-powerful Death Star that must be destroyed), but there are many other influences and references that genre fans can enjoy identifying, if they want to.

Yet focusing on these influences risks overlooking what might be most original, and potentially game-changing, about The Creator, which is how it was, well, created.

Edwards’ background is in VFX. As is well-known, he basically single-handedly crafted the impressive special effects in his debut feature Monsters (2010) – well-worth catching up on if you haven’t seen, and which shares several themes with his latest film.

Monsters was made for less than $500,000; The Creator reportedly cost $80 million but looks like something typically made by Hollywood for $250 million or more. While the storied ILM did most of the effects, Edwards was able to achieve his vision by effectively reverse engineering the typical (sci-fi) filmmaking process. Rather than relying on expensive studio sets and green screen work, he deployed a small crew and was able to travel to (it’s said) 80 locations to give The Creator an expansive, epic scope, only adding in the effects after the film had been fully edited (places used included Nepal, the Himalayas, Indonesia, Cambodia, Vietnam, Tokyo, and across Thailand). He even shot on a Sony FX3 – a prosumer camera – with some beautiful and spectacular results.

This is where The Creator really distinguishes itself, in being an original (meaning, not based on some existing intellectual property), non-sequel/non-franchise, theatrically released serious sci-fi film – here in the 2020s when arguably we need sci-fi more than ever to help us anticipate some potential dark futures ahead of us.

Of course, there’s a long history of inventive, low-budget sci-fi (and genre movies generally), but ironically even with (or partly because of) the CGI revolution, what we’ve been losing are the kinds of mid-budget, challenging, socially critical sci-fi movies that flourished from the end of the 1960s and into the 1970s (the kinds of films I discuss in my forthcoming book). When you’re spending hundreds of millions of dollars, commercial logic dictates that you must veer towards crowd-pleasing acceptability (but which ultimately probably ends up pleasing no-one). The Creator – certainly in its realization, if arguably less so in its revelations – shows how it’s once again possible to produce serious science fiction on film and still (hopefully) make money. In this respect at least, it presages a bright future.

Come With Me If You Want To Live: The Future as Foretold in Classic Sci-Fi Films is published in November 2023 from Lexington Books.

“Now read on… into the fantastic world of the future!”

Here’s the draft preface to the book I’ve completed recently. You’ll hopefully get the idea of the book from this - let me know what you think!

Here’s the draft preface to the book I’ve completed recently (it’s currently out to publishers and agents for consideration). You’ll hopefully get the idea of the book from this - let me know what you think!

“That’s how each of the three sections (robots, cities, space travel!) of The Usborne Book of the Future begins. Written by Kenneth Gatland and David Jefferis, it was published in 1979, and it was one of my favorite books when I was growing up.

Nothing dates as fast as ideas about the future. And you can certainly play that game with the Book of the Future, subtitled A Trip in Time to the Year 2000 and Beyond. So no, our houses don’t yet have automated servants handing out trays of drinks, and there aren’t robotic forest firefighters. Or everyday Space Shuttle flights, space elevators, factories in orbit, or massive domed cities, let alone an Olympics on the Moon (predicted for 2020). Many of the timescales for new technologies are way off, although maybe one day we will inhabit cities in space (indeed, some of today’s billionaires are counting on it).

And yet, as anticipated in The Book of the Future, we do carry minicomputers in our pockets, much more powerful than the ‘risto’ watches featured in the book, and our homes are full of inter-connected gadgets. Robots have “increasingly take[n] over the jobs of skilled engineers in factories.” Artificial intelligence is advancing into our lives. Shopping is increasingly online (The Book of the Future predicted that TVs will be “used to order shopping via a computerized shopping center a few kilometers away”). Electric vehicles will eventually become widespread (the book predicted an “almost totally electric world”). Computerized weapons systems are shaping the future of war. “Electronic conferencing” is finally common, but not, as we now know, because of “convenience”. And some people are experimenting with sea-borne living, like the floating pyramid cities featured in the book.

That it got at least some of these predictions largely right isn’t surprising. The Book of the Future was based on the research of scientists and organizations including Bell Aerospace, Boeing, and NASA, alongside Arthur C. Clarke and Omni magazine. But there were other things about the future the book spent much less time discussing.

I was born in 1971. The generation before me, some of them, could still be excited about The Future. As in The Book of the Future, they could believe they would go into space and eliminate poverty, crime, war and disease on Earth. A generation later, as a child I still read comics about daring space adventurers, but I also knew they had a decidedly retro, 1950s feel to them. They were yesterday’s future, not the actual future.

As I grew up, the future seemed to get darker, it was darker: the possibility of nuclear annihilation in the Second Cold War, demonstrations, strikes, mass unemployment, increasing inequality, and the growing sense, as the punk movement put it, of ‘no future’. As we’ll see, this was reflected in fictional depictions of the future. From the late 1960s onwards, there was a new adultness in science fiction, including at the movies. Technical advances in filmmaking helped, but the real progress was in its subjects: there was less about fantastical aliens, and more fatalism about humanity and its future (or lack of it).

Today, young people are even more anxious about what’s to come. Unfortunately, it’s probably worse than most of them imagine. In their future, they could see civilization collapse, due to everything from climate change to wars over dwindling resources. In some of its fundamental warnings, the dystopian sci-fi of the 1970s is fast turning into fact.

To understand what happened to the future, we have to go back to when I was young, to a point when two very different futures were possible and the choice between them was still being made. In between its Lunar Olympics and interstellar starships, what really strikes me looking back at The Book of the Future (and at the time, as I remember), is the double-page spread titled “Two trips to the 21st century”, and the stark contrast it presents between a “Garden city on a cared-for planet” or a “Polluted city of a dying world.”

In the latter, there’s over-population, vehicles trundle along powered by gasoline (alternatives were not pursued, leaving no options as oil runs out), the environment is dying, the air is a chokingly thick brown orange (people wear gas masks), urban infrastructure is decaying, and people are out of work and under-fed. Fake plastic trees line the roads. But in the former, fumeless hydrogen and electric powered vehicles glide through a refurbished, greenified city beneath a monorail and alongside pedestrian and cycling lanes. The air is a fresh spring blue. The plants and trees are a vibrant green.

There were two possible futures back then, so it seemed, one darkly dystopian, the other much brighter – not a whizzy 1950s Jetsons techno-utopia, but still a pretty good one.

What I realize now, and we’ll discuss in this book, is that these two futures were based on predictions set out in landmark publications like The Limits to Growth, published just a few years before in 1972. And we’ll examine how, contrary to their fierce critics at the time, the scary predictions made in these publications are increasingly coming true.

We didn’t heed these warnings, or those depicted in popular culture ever since. This book is about why. The short answer is that, starting in the 1970s, an organized and well-funded campaign was mounted against recognizing the threats we faced, and it succeeded in persuading people the future would effectively take care of itself.

Indeed, we’ll see how it was these predictions of a dark future that helped to propel – in some ways helped to create – a new political movement, which until the 1970s was relatively marginalized. What’s been neglected in previous histories is how its attractive promises – that there were no limits to growth, and technology would solve the problems we face – were crucial in bringing them, and a new type of politician, to power. And so we set off towards one of the two futures sketched in my children’s book – the wrong one.

We can’t say we weren’t warned, including by some of the best science fiction films of the past fifty years that depicted future dystopias, which we’ll use here to discuss what’s going to happen next. We’ll also uncover the surprising hidden meanings of these films, meanings that are now more relevant than ever (there are major spoilers for the films).

It’s not the future we want (most of us, anyway), and it’s not the one we were promised. But the more we understand what’s coming, the more we might be able to prepare for it.

So, read on, not into the fantastic, but definitely into the dramatic, world of the future…”

Read the Introduction from Stay Alive: “Real or not real?”

Here’s an edited version of the introduction to my new book, Stay Alive: Surviving Capitalism’s Coming Hunger Games - out now from Zero Books.

Here’s an edited version of the introduction to my new book, Stay Alive: Surviving Capitalism’s Coming Hunger Games - out now from Zero Books.

“There must be some special girl. Come on, what’s her name?”

The first book in the series, The Hunger Games, introduces us to Panem through Katniss Everdeen, a 16-year-old woman. In just a few pages, we learn about the world she wakes up in everyday. We enter the deprived, slave labor prison of District 12, where most people don’t have enough food to eat, and the Seam, the dirt poor coal-mining area where Katniss lives with her mother and her younger sister Prim.

Katniss has lost her father in a mine explosion a few years before. We’re given a sense of her psychological damage from poverty and loss. Katniss’s mother is “blank and unreachable” after her husband’s death. Katniss is in many ways also numb to the world. She’s annoyed at her mother for shutting down, but she doesn’t really see how she’s done the same.

Katniss is a survivor, practically in using her hunting skills to secure a little more food for her family, and emotionally in finding her own ways to cope. Given the knowledge she’s inherited from her father, Katniss could provide for her family, but hunting is illegal.

The Hunger Games isn’t just the brutally honest name of the annual fight-to-the-death competition organized by the Capitol, the city that dominates Panem. It’s the way that its elite controls the districts. Starvation, scarcity and minimal rewards doled out to subservient districts; the Capitol uses hunger as a weapon against the masses. It’s also a powerful metaphor for the economic system we live under today, so much so that “the Hunger Games” has now become shorthand for any especially brutally competitive environment or economy.

Despite this, Katniss is a natural rebel, though she doesn’t think of herself that way (in time she will, though). She finds the weak spots in the fence surrounding the district and escapes into the woods to hunt, but really just to find a few hours of freedom in her highly-surveilled society. And yet, Katniss’ acts of everyday rebellion will have major consequences. They will come to represent the seeds of a different world.

“It’s to the Capitol’s advantage to have us divided among ourselves”

Like all of Panem’s subjects, Katniss has learned it’s not safe to criticize the system. She’s somewhat aware of the impact this has had on her, to “hold my tongue and to turn my features into an indifferent mask so that no one could ever read my thoughts.” Looming over her, over all of the young people who live in the districts, is the Hunger Games, a brutal televised fight to the death. Today is reaping day, the day of the public lottery for participation in the Games.

The odds that any given child will be selected for the Games are relatively low - lower in districts with large populations (unlike the small District 12). But the fear is real. Even here, the Capitol reinforces its control through division. Other districts, those more favored by the Capitol, are better trained to compete. Their tributes, called “careers,” even look forward to being chosen for the Games.

The Seam, where Katniss lives in District 12, is the poorest of the poor. But some families in District 12 are comparatively better off, for example those who run small businesses. They can reduce the likelihood that their children will be selected for the Games, whereas the likes of Katniss and her closest friend Gale are forced through threat of starvation to increase their odds of selection in exchange for desperately needed food rations. As Gale says, it’s the Capitol’s strategy to divide the districts between each other, and within them.

“You sit on a throne of lies”

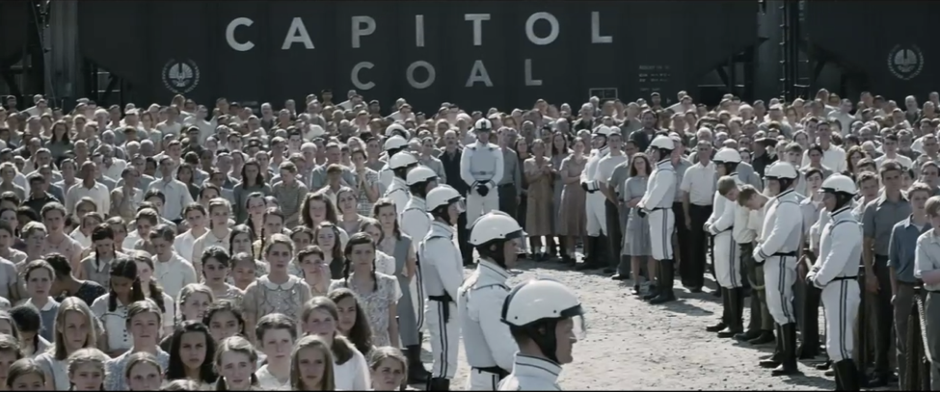

The film of The Hunger Games starts differently from the book. After some introductory text, we open on a discussion between Caesar Flickerman, the Capitol’s television host for the Games, and Seneca Crane, the Head Gamemaker who designs the Game arena. They’re discussing the “bonding importance” of the Games, how it’s “our tradition...the way we’ve been able to heal.” At first the Games were a reminder of the first rebellion and the “price the districts had to pay,” as enshrined in the country’s Treaty of Treason, but now apparently it’s “something that knits us all together.”

The Capitol audience, comfortable in their plush auditorium, applauds warmly. Caesar asks Seneca what describes his “personal signature” as Gamemaker. Cut to a horrifying scream and a bleak shot of District 12. It’s Prim, waking up on the day of the reaping after a nightmare. What defines the Games, this year and every year, is not healing, but horror.

This new scene added for the film emphasizes the political nature of the story, starting in the Capitol’s construction of a self-justifying national myth, its attempt to rationalize oppression and exploitation in the name of order and unity. But what we mostly see is how the system affects the young people existing in the shadow of the Games, the horror they experience in the arena, and the psychological trauma of trying to survive under the Capitol’s rule.

“Well, that’s a sunny view of our situation”

Later, during the reaping ceremony (in the film version), a propaganda video is shown to the districts. President Snow, the ruler of Panem, provides the voice over, reiterating the “hard fought, sorely won” peace that his new order has ensured. Of course, this is only how the Capitol wants the districts to remember “our history.”

The Hunger Games takes place at an unspecified future date, in the dystopian, post-apocalyptic nation of Panem, located in what is now the United States. The country is smaller than today, geographically and demographically. Large areas of land were made uninhabitable by rising sea levels and many people died (for example, the population of District 12 is said to be just 8000 people).

Panem consists of the wealthy ruling Capitol city, located in the Rocky Mountains, surrounded by 12 (originally 13) poorer districts. Katniss’ District 12 is located in today’s Appalachia. The furthest from the Capitol, it specializes in coal mining. District 13 was a center of military-industrial production. When the Capitol crushed the rebellion, it reduced District 13 to ashes.

The government is a dictatorship, a surveillance state in which the districts are forced into subservience to the Capitol, expected to provide goods in exchange for “protection,” for peace and prosperity. But only the Capitol is lavishly rich and technologically advanced, while the districts survive in poverty and distress. In place of the actual history of America/Panem, the Hunger Games is part of a national myth, told by self-serving elites.

“These things happen in war”

Panem is founded on a core conservative idea, one that still holds a powerful grip on today’s politics: that the state restrains us from all-out civil war. This was first set out by the English philosopher Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679), particularly in his most famous book Leviathan (1651). Hobbes was informed by the English Civil War or civil wars of 1642-46 and 1648-51 – he often uses the word “rebellion” – that led to the execution of the king and the declaration of a republic.

At the time, England was divided, politically, economically, socially, religiously, then militarily. Hobbes’ argument was rooted in a deeply pessimistic view of human behavior, dressed up in some crude “science” (as conservatives still do today). We are driven by greed and fear. Without an authoritarian state, we compete, often violently, to secure the necessities of life and seek reputation (“glory”), both for its own sake and for greater security. Hobbes’ state of nature is perpetual strife, endless dark days comprising a “war of all against all,” leavened only by temporary alliances to stave off graver threats and imminent perils. Hobbes thought that the inevitable condition of humankind was one in which life is “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short,” a relentless quest for power that “ceaseth only in death.”

In such bleakness, our only “hope” is all-powerful authority. People must surrender their power to the ultimate peacekeeper, the sovereign ruler. But in reality, this idea just normalizes the actions of some selfish, amoral people as “natural,” and supports exploitation and right-wing authoritarianism, even fascism.

“I’m sick of people lying to me for my own good”

There’s a deeper, psychological explanation for this attachment to authoritarianism.

One of the thinkers we’ll refer to in this book is Alice Miller, a Polish-Swiss psychologist/psychoanalyst noted for her work on parental child abuse, sometimes called “controversial” because she was so direct in her challenge to abuse and its links to authoritarianism.

In For Your Own Good (1980), Miller introduced the concept of “poisonous pedagogy” to describe the child-rearing practices prevalent in Europe, especially before the Second World War. She believed that the pain inflicted on children “for their own good” was parents unconsciously re-enacting the trauma inflicted on them when they were children, continuing the cycle of trauma down generations.

Breaking Down the Wall of Silence (1990) is perhaps Miller’s most explicitly political book. Written in the aftermath of the fall of the Berlin Wall, Miller takes to task the entirety of human culture. The “wall” is the metaphorical barrier behind which society (academia, psychiatrists, clergy, politicians and the media) seeks to protect itself by denying the mind-destroying effects of child abuse. Historically, children were seen as less than human, as evil wretches in need of constant coercion and control. The goal of child-rearing was to stamp out willfulness in children, to crush their spontaneity and spirit, thought necessary in order to make them upstanding and virtuous citizens.

To Miller, the command to “honor your parents” leads us to accept and repeat abusive parenting and direct our unresolved trauma either against others (through war, terrorism, delinquency) or ourselves (in eating disorders, drug addiction, depression). This is also the root of political authoritarianism: dictators seek to pass on their trauma to society, and we accept their abuses of power because of our indoctrination into the legitimacy of the harsh parent. Only by becoming aware of this can we break the chain of violence.

In The Hunger Games, the Capitol claims the right, the necessity, to rule over the otherwise disobedient citizens of Panem. Panem needs to punish its children to avoid further conflict. Trauma is passed down and legitimized. And Katniss, like her peers, is emotionally numb and politically passive, despite her repressed rage at the cruelty of the Capitol. As Miller wrote in Breaking Down the Wall of Silence, “The reality of adult cruelty is so beyond their comprehension that the child is in a state of constant denial in order to survive.”

Miller didn’t accept that we’re naturally evil. If we recognize the causes of trauma and the roots of authoritarianism, we can heal and recover. This is the emotional journey that Katniss will go on, and perhaps the one we all need to undertake.

“And they say no one ever wins the Games”

A much more benign view of how we can and do act can lead us to envisage a very different kind of society, in which centralizing power is not the solution, it’s the problem. If this is the political journey that Katniss will go on, in another way, as we’ll see, she was there from the beginning.

Another purpose of Hobbesian propaganda is that people will accept shortages, hardship, cruelty, misery and the curtailing of their freedom if you convince them they’re in a perpetual state of war, or would be without the powerful parental state. As we’ll see, even though many people in the districts don’t fall for it, this ideology helps to justify their privation.

Of course, not all of our societies suffer under authoritarian regimes, despite Hobbesian thinking still being prevalent. But environmental, economic and political collapse, and the fear and chaos they will bring – our own coming hunger games – are likely to lead us toward our own version of Panem.

“No, I want you to rethink it and come up with the right opinion”

The Hunger Games starts with a Hobbesian state, but never accepts it. This is based on a fundamentally different view of human nature to the Hobbesians. Not a naive view – Collins depicts the cruelty that people can inflict on others under an authoritarian ideology. But a view that suggests how the state is the real source of violence in society and how it engineers conflict as a means of control.

The alternative view is that our environment shapes how we behave, that left to our own devices we are more likely to find ways to cooperate peacefully, even to sacrifice ourselves for others, than we are to engage in an endless war against all. What raises The Hunger Games above most dystopian stories is that it also depicts how goodness can flourish even in the most dehumanizing circumstances.

It’s possible to imagine a peaceful Panem without the state, a society of mutual trade and cooperation, of solidarity and fraternity. But Katniss can’t allow herself to imagine this world for more than a moment, not because it would be against nature, but because the state would punish them harshly for even trying to live differently. She might be a survivor, but she’s mired in resignation. Before the reaping, Katniss listens to Gale’s dreams of escape, but can only respond that it’s impossible, to leave their families, to put them at risk, let alone to hope that another Panem is possible.

“What am I supposed to do? Sit here and watch you die?”

Some dystopias drop us into howling post-collapse wastelands in which the problem is the lack of government, a lack of any institutions really, or travel through lawless cyberpunk cityscapes in which there’s a lack of a state standing up to towering corporations. Hobbes would surely recognize his state of nature in these stories.

As we’ll see, these views of human nature are also fundamentally about capitalism. The rationale for the Hobbesian state is also used by conservatives to justify an exploitative economic system in which elites dominate and the poor suffer. It’s just as much a lie as Panem’s propaganda is for punishing its districts.

But for now, the Capitol is in control. And it’s Katniss’ sister Prim, in her first reaping, who’s selected for the Games.

“I volunteer!” I gasp. “I volunteer as tribute!”

When Katniss volunteers for the Games in place of her sister, the crowd understands it’s suicide, given her district’s poor record in the Games and its disadvantages against the other districts. Despite the Games supposedly being a national pageant, they respond with “the boldest form of dissent they can manage. Silence. Which says we do not agree. We do not condone.” Later on, Katniss will learn that many other districts are also ready to defy the Capitol.

Although she doesn’t intend it, Katniss’ instinctive reaction to volunteer represents the start of a revolution, a spark that will ignite a fire that will eventually engulf Panem. What that revolution means, and what she’s really fighting for, are critical questions at the heart of The Hunger Games.

“She has no idea, the effect that she can have”

And then, something unexpected happens. Almost every member of the crowd touches the three middle fingers of their left hand to their lips and holds them out to Katniss. It’s an old, rarely used gesture in District 12. It means a combination of thanks, admiration and goodbye to a loved one.

The Hunger Games struck a chord from the start. The first book in the series, published in 2008, was an instant bestseller, appealing both to teenage readers and adults. In 2012, the first of four films based on the novels was released (the final book was split into two films), starring Jennifer Lawrence as Katniss. The series has earned $3 billion at the worldwide box office. Clearly, the story has resonated with audiences, particularly young people. The question is why, and whether it means anything politically.

“I really can’t think about kissing when I’ve got a rebellion to incite”

Some commentators assumed its appeal centered on the love triangle between Katniss, Gale and fellow District 12 tribute Peeta. But this isn’t the focus of the story, it’s a subplot to bigger political questions, notably how to survive under an authoritarian regime, the price people are prepared to pay to bring it down and whether this corrupts the post-regime society they long for.

Really, it’s more of an anti-romance. Katniss is a rounded, believable, brave, compassionate, flawed, self- doubting character, who continues to inspire young women in particular, personally and politically, not because she’s flawless, but because she isn’t.

Katniss is surrounded by expectations about what she should be and how she should act. As we’ll explore, the reality TV show of the Games and state spying means that Katniss and her peers are often acting for the audience, a pressure felt by young people in our own age of social media surveillance. But this means that Katniss continually distrusts the motives of Peeta in particular. She even often doubts her own motivations.

“This isn’t just adolescent, it’s insubordination”

In how young people are contained and punished, The Hunger Games also reflects adult fears of adolescence as a powerful destabilizing force. Even in her hopelessness, Katniss challenges the fixed boundaries of her world, literally in the sense of temporarily escaping the Seam to hunt and feel free. But to stop here ignores the obvious themes of the story. As Rolling Stone put it, “It’s about something pertinent, the mission to define yourself in a world that’s spinning off its moral axis.” It isn’t a high school drama, it’s a political coming-of-age story about class and conflict, for its characters, and for its audience. As Suzanne Collins has said, “I don’t write about adolescence. I write about war. For adolescents.”

“That’s why we have to join the fight!”

Talk about great timing. The first book was published in the midst of a global financial crisis, from which the resulting austerity was inflicted mainly on the young, poor and minorities. Much of The Hunger Games’ generation has lived with a lack of opportunity and growing inequalities in generational wealth and power, alongside war and terror and reality-twisting politicians.

As many reviewers have noted, Collins is a very deliberate world builder, with lots of historical references and allusions. But the story really resonates because it looks forward. The future in the story isn’t really so futuristic, it’s fast oncoming social fact. Young people are offered up as sacrifices for the elite-controlled state. They face a punitive and divisive economic system, environmental collapse, authoritarian populist politics, sophisticated media manipulation and total surveillance. For Americans and others who don’t recognize the dystopia that’s already here, let alone the one to come, it’s either because they feel safely ensconced in the Capitol or because they’ve already accepted its Hobbesian propaganda.

“I’m going to be the Mockingjay”

The Capitol’s ritual televised sacrifice of tributes, the watching of which is mandatory, demonstrates its domination of the districts. The Games promote a brutal competitive individualism that seeks to obliterate all other values, and humanity itself. They exert the Capitol’s control beyond its economic exploitation of the districts, into peoples’ ability to envision an alternative future free of domination. However, the spectacle of the Games also creates an opportunity for the subversion of the Capitol’s story of subjection for the “good of the nation,” ultimately into one of personal sacrifice, of love, demonstrating a different kind of unity. This is the spark that Katniss sets off when she volunteers.

“They just want a good show, that’s all they want”

We might be suspicious of Hollywood selling us ‘rebeltainment’. The criticism is that The Hunger Games and its imitators might represent some of the fears, frustrations and anxieties of today’s precarious young proletarians, but it doesn’t really name the system of oppression or its possible replacement.

Even if this were true, if Hollywood is the creative Capitol, we can claim and subvert its stories. Katniss introduces a new story to the Games, of defiance in place of deference, cooperation instead of competitive individualism, self-sacrifice rather than subservience. Once these seeds have been sown, it’s the Capitol that becomes terrified of their reaping.

It’s better surely to act like the rebels in the story and recognize when some useful revolutionary symbolism has been thrown our way. Or as Mark Fisher (“Precarious Dystopias”) puts it, “[I]f blockbusters about class revolution perform their ultimate ideological function – maintaining business as usual – by encouraging our cynical distance from those underlying fantasies, the truly subversive thing is not to disregard the dream but to stick to the desire that sustains it.”

Just as Katniss despairs at the start of the story, the Capitol depends on us believing that change is impossible, that the system is too strong. But unbeknown to her and Gale and Peeta, the revolution is about to begin, the districts are more ready to revolt than they know, and the Capitol is more vulnerable than they assume. Sometimes it just needs someone to supply the spark.

“If desperate times call for desperate measures, then I am free to act as desperately as I wish”

Which is why The Hunger Games is about containment, and the fundamental fear that Capitol elites have about the people of the districts. Katniss, the other tributes, the districts, even the victors – all are constantly contained and herded, by fences, borders, Peacekeepers, artificial arenas and deadly hazards, pervasive propaganda and reality TV productions.

Today’s young people will live in a future of walls, of containment driven by collapse, environmental destruction, scarcity and a sociopathic elder elite’s fear of losing power. More than three decades after the fall of the Berlin Wall, young people are unconstrained by fears of authoritarian “socialism.” New walls need to be constructed, of individualism, intolerance, hopelessness and passivity. Working out what’s real and what’s Capitol propaganda will be crucial, the first step to surviving the coming hunger games. And let’s remember that the Capitol wouldn’t bother with its propaganda if it didn’t fundamentally fear us.

In The Hunger Games, Katniss is the last person to recognize her significance, and our potential to bring down the walls. The Capitol and the rebels identify her power long before she does. What she wakes up to is not the full horror of the system, she’s more than aware of that. No, what she comes to understand is that, in the world of Panem, survival is unavoidably a revolutionary act.

Stay Alive: Surviving Capitalism’s Coming Hunger Games is published in paperback and e-book by Zero Books and can be ordered from the following places now:

“At this point, unity is essential for our survival”

On International Workers’ Day, also known as Labour Day or May Day in many countries, here’s a short excerpt from chapter nine of my new book, Stay Alive: Surviving Capitalism’s Coming Hunger Games.

On International Workers’ Day, also known as Labour Day or May Day in many countries, here’s a short excerpt from chapter nine of my new book, Stay Alive: Surviving Capitalism’s Coming Hunger Games:

There was always an alternative to capitolism’s Hobbesian order based on fear and obedience. It’s solidarity, and contrary to Capitol propaganda, it’s entirely natural to us.

As Astra Taylor and Lean Hunt-Hendrix note (“One for All”, New Republic, 26 August 2019), as a social theory, this idea first emerged in the legal texts of the Roman Empire, although of course as a social practice it goes back long before that; it’s how we’ve survived as a species. In the Roman era, when people held a debt in common they were said to hold it in solidum. Being in communal debt was the basis of solidarity, a very different kind of debt to capitalist hierarchical debt. If one individual faltered, its members would either bail each other out or default together.

In its original formulation, solidarity was a common identity underpinned by collective indebtedness and obligation, shared responsibility and risk, interdependence and mutual aid. Terms like “bonds,” “trust” and “mutual funds” are now used by bankers to describe financial mechanisms. But real solidarity, in contrast to modern contracts, has to be cultivated. It’s the practice of creating social ties, of inventing collective identity.

“In the early nineteenth century, solidarity became central to the growing labor movement. Craftsmen and laborers from a range of industries, who once saw themselves as unconnected, began to share a larger common character as workers. As industrialization spread, this new working class strengthened their common bonds through acts of resistance and strikes. Solidarity was also central to the creation of welfare systems and social safety nets.

These understandings of social belonging have been eroded under the corrosive pressures of contemporary life. Modernity made the individual sacred, but also separated, isolated, as we saw in the statistics on mental health. Capitol propaganda and division has also de-socialized us, through economic stratification, privileges for some, and shaming the poor.

Today, “solidarity” is most associated with inter-group expressions of comradeship, for example international campaigns in support of groups resisting oppression. Such campaigns say we do not agree, we do not condone. (As noted in the prologue, solidarity is also crucial to direct action movements, as in the Hong Kong protests.) Perhaps, in place of nationalistic supposedly unifying myths, we might be able to tell alternative stories, including for democratic self-governance at a global level. To Hauke Brunkhorst (Solidarity: From Civic Friendship to a Global Legal Community), this might be being modeled in recent global protest movements, the beginning perhaps of a transnational civic solidarity.

The enormous challenges we face, from capitalist authoritarianism to climate change, require that social movements forge a radical solidarity. Building of bonds and diverse coalitions is essential to the struggle for a just world. The Capitol will of course push back, buying off some of us, but mostly trying to turn us on each other, to keep their games going. But there is no survival, let alone freedom, without each other.

Stay Alive: Surviving Capitalism’s Coming Hunger Games is out now in paperback and e-book from Zero Books and can be ordered from the following places:

The four words that explain why The Hunger Games resonates politically with young people

(Hint: It’s not “Welcome to the Capitol.”)

I’d suggest the words are: the game is rigged.

Talk about great timing: the first Hunger Games book was published in the midst of a global financial crisis - literally on the day investment bank Lehman Brothers declared bankruptcy and the crisis entered its most acute phase. The resulting austerity was inflicted mainly on the young, the poor and minorities. Much of The Hunger Games’ generation has lived with a lack of opportunity and ever-growing inequalities in generational wealth and power, alongside war and terror, and reality-twisting politicians.

Put simply, many young people don’t believe they stand a fair chance anymore. Nor do they think this is likely to change; we’re probably going to see the same thing happen in the wake of the pandemic, in which again, already, the young, the poor and minorities have been hardest hit economically.

And what should worry elites most is that many young people also know why.

This is from chapter five of my forthcoming book Stay Alive: Surviving Capitalism’s Coming Hunger Games, out on 30th April/1st May 2021:

“The Games aren’t just a distraction. They also perform a propaganda role in establishing a dominant set of social values, values that legitimize the state’s brutality and enforced inequality, and corrode the natural social solidarity that might threaten the Capitol. The Games model and promote, attempt to naturalize, the Capitol’s broader ideology: brutal competitive individualism for the masses, eternal punishment for the poor, and a hopelessness that they can ever really win. They are the engineered embodiment of the degradation for which the Party in Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four strives: “In our world there will be no emotions except fear, rage, triumph, and self-abasement...Always, at every moment, there will be the thrill of victory, the sensation of trampling on an enemy who is helpless.”

Even the Capitol’s presentation of the Games – two young tributes from each district “to be trained in the art of survival and to be prepared to fight to the death” – is deceptive. The environment of the arena provides the illusion of choice: competitors can adopt different strategies and use whatever skills they like. They could even make the “choice” not to kill. But as noted, its meritocracy is a myth, since the career tributes typically win, and sponsors typically favor those most likely to prevail. It’s possible to grant the Capitol credit that this may also be a conscious part of its ideological design for the Games, a way to reinforce that the game is rigged against the poorest districts from the start.

But in theory at least, the Games are every man and woman (child, really) for themselves (the supposedly natural elite of the Capitol never puts up its own competitors). The objective is to crush feelings of solidarity and interdependence between the districts, which is to say, the ordinary working and middle class (such as they are) of Panem. Much as how modern states use class, religious, ethnic and other differences to divide the working class and hinder their organization, Panem uses the Games to foster competition rather than cooperation between the districts, despite the fact that they have more in common with each other than anyone inside the Capitol’s citadel. They literally get the districts to fight against each other.”

Stay Alive: Surviving Capitalism’s Coming Hunger Games is published in paperback and e-book in April/May 2021 by Zero Books and can be pre-ordered from the following places now:

Read the preface from Stay Alive: “If we burn, you burn with us”

Why The Hunger Games series continues to resonate with young people and protest movements today.

A flag reading "If we burn, you burn with us," erected outside Hong Kong's legislature, July 1, 2019.

In July 2019, a new theme park opened in the People’s Republic of China. Located in Hengqin, Zhuhai, in the Guangdong- Hong Kong-Macau Greater Bay Area, Lionsgate Entertainment World is a movie-themed “vertical theme park” spanning 22,000 square meters of indoor space. Designed to appeal to the “young adult dating crowd,” it features attractions based on franchises owned by the major American media corporation. These include The Hunger Games, Suzanne Collins’ hugely successful future dystopian fiction series about a totalitarian regime and its annual state-sanctioned child murder pageant.

As described by Forbes magazine, “With an entire level devoted to The Hunger Games, visitors will be immersed in the wealthy Capitol City with a gold and marble streetscape, a themed gourmet restaurant, a bakery, and a hair salon inspired by the outrageous styles in the film.” Inadvertently echoing the desperate enthusiasm of Effie Trinkett (a character from the series), Selena Magill, General Manager of Lionsgate Entertainment World, exclaimed that: “We expect guests in China and all around the world to enjoy sensational experiences here that they won’t soon forget.”

For a more authentic experience, fans could travel just an hour away to Hong Kong, where the Beijing-backed government was clamping down on the protest movement led by young people against very real encroaching Chinese tyranny. At times the streets of the city resembled scenes from the films, with Hong Kong police, acting like The Hunger Games’ perversely named Peacekeepers (state military police), beating young people in the streets and firing tear gas indiscriminately into crowds, while protesters brandished bows and fire-dipped arrows.

The loosely coordinated but often highly disciplined protesters, drawn from the self-described “cursed generation,” used social media savvily, often employing tropes from popular culture, including spray painting one familiar (to Hunger Games’ fans) slogan on walls and subways: “If we burn, you burn with us.” The protesters wore black, like the forces of the Mockingjay revolution (the rebellion in The Hunger Games), while pro- government agents and Triad thugs wore white, like President Snow (the dictator of the series’ fictional country of Panem) and his brutal army of Peacekeepers.

This wasn’t the first time protesters had drawn on the series. In 2014, during the Umbrella Revolution, they’d used the three- finger salute from the story, a symbol of solidarity and defiance. After the failure of their first rebellion, the protesters left signs reading “We’ll be back.”

They kept their promise. The year 2019 saw months of sustained protests and mass marches. But the Hong Kong and international business community largely looked on, while investors only fretted about the impact on China’s plans to turn the region into a financial and technological hub to rival Silicon Valley – a gleaming twenty-first century Capitol (the wealthy ruling city of Panem), surrounded by servile industrial districts and factories with “suicide nets” to stop workers killing themselves.

The protests were for freedom and democracy, a last chance for basic rights. But they also represented anger at Hong Kong’s largely unregulated capitalism, with young people priced out of the most expensive housing market in the world and seeing few opportunities in their future, all the while being ordered to act as “patriotic citizens” by the super-wealthy political-business elite who run the city.

An uber-rich ruling class gorge themselves in a futuristic playground, while working people struggle to survive in exploited rural areas. The possibility of revolution is only a distant memory, a forgotten hope kept at bay by brutal policing, aching poverty and a rigidly segregated class system. The Hunger Games could be seen as a critique of states like China – an authoritarian, propagandized, militarized, state capitalist economy, which runs prison camps for political dissidents, including using forced labor to supply goods for Western corporations. But that wasn’t the series’ aim. Its setting is a post-collapse North America. It’s both a warning about the near future and a cutting critique of the present-day United States, of reality TV politics, the demonization of the poor, state violence and oligarchy.

When The Hunger Games began in 2008 – it’s since become a defining story for a generation that’s grown up with economic crisis and never ending war – many commentators lumped it in with other young adult genre fiction such as Twilight and Divergent. But The Hunger Games is political. It’s about an elder elite that uses state power, a compliant media and violent spectacle to pacify its population. It’s about how a rebellion is sparked by defiance and spreads through subversive symbols, while the regime responds in the only way it knows.

The year 2019 saw youth-led revolts in other countries as well, from Chile to Lebanon, Thailand to Columbia. Despite different local flashpoints, underlying all of them were extreme inequalities which especially disadvantage young people, and the willingness of elites to crush any challenges to their power. The world hadn’t seen a wave of street protests like this since the late 1980s, surpassing the scale of the Arab Spring protests of the early 2010s.

In an important sense, The Hunger Games predicts how regimes around the world are likely to respond to increasing youth-led protests against their power. It’s about collapse, war, rebellion, trauma and recovery. It’s dark, emotionally and politically truthful, and while it doesn’t flinch from the horrors of its setting, it’s also ultimately, eventually, realistically hopeful. It’s a story about how regimes fall, but how the revolution against power and exploitation can never end. And with the climate crisis and environmental disaster, it’s about a coming future of enforced scarcity and segregation, and an emerging form of authoritarian statism we’ll call capitolism. It’s the story of our times, and most likely of our future as well.

The real hunger games are just beginning. We need to return to Panem.

Stay Alive: Surviving Capitalism’s Coming Hunger Games is published in paperback and e-book in April/May 2021 by Zero Books and can be pre-ordered from the following places now:

10 ways The Hunger Games is our present – and our future. #10: “Because that’s what you and I do. Protect each other”

The real revolution that lies hidden at the heart of The Hunger Games

The real revolution that lies hidden at the heart of The Hunger Games

This is a series of blog posts based on my new book, Stay Alive: Surviving Capitalism’s Coming Hunger Games, published in April/May 2021 by Zero Books.

In The Hunger Games, young people are offered up as sacrifices for the elite-controlled state. They face a punitive and divisive economic system, environmental collapse, authoritarian populist politics, sophisticated media manipulation and total surveillance. For Americans and others who don’t recognize the dystopia that’s already here, let alone the one to come, it’s either because they feel safely ensconced in the Capitol or because they’ve already accepted its Hobbesian propaganda.

It’s the authoritarian populists of the right who’ve benefited the most politically from early collapse. As it advances further, collapse will tear to pieces the left’s desire to direct an essentially stable state to share wealth much more widely. Collapse is corroding social trust, tolerance, truth. Crisis and scarcity are being used to spread fear and scapegoating. The elite’s endgame is working.

As our societies struggle to respond, people’s despair and disengagement with democracy will continue to grow. Confidence in it has already weakened across Western countries; this has increased political instability and made populaces more prey to demagogues and disinformation. More people will look to seemingly ‘strong leaders’ and reject liberal principles in favor of promises of greater ‘security.’

Unfortunately, because of early collapse, our age of conflict, anger, polarization and denial is the worst possible context in which to try to engineer a more rational future. The Capitol is winning collapse. It looks like the districts have already lost.

In the backstory to The Hunger Games, during the Dark Days, the war between the Capitol and the districts nearly wiped-out humanity. At some point the districts were forced to surrender, perhaps to save whoever remained. An armistice was signed, resulting in the Treaty of Treason. Perhaps the ultimate advantage held by the Capitol is that it’s happy for people to die to protect its dominant position in Panem. Just like elites in our world.

For the center-left, there will be no steady progress toward the perfect social democratic, let alone democratic socialist, order. For the radical left, there will be no universal global revolution. Once, we might have thought that if we want to live in a different world, this world has to end. Now, this world is going to end, but in totally inhospitable ways. The challenge is how we might survive, and maybe one day, begin to build different worlds.

But The Hunger Games also contains the seeds of a different, better world, and it plays out starting in the Arena. In the Games, Katniss befriends a young girl from District 11 called Rue. When they become allies, they learn more about each other’s districts than they’ve ever been taught in school or through Panem’s state-controlled media. This begins to bridge the system of segregation: a cross-racial alliance between two of the poorest districts in Panem. Katniss and Rue recognize their common oppression under the power structure. This is not how the game is supposed to be played.

Then, Rue’s death politicizes Katniss, or rather, brings to the surface her buried emotions. It breaks through Katniss’ wariness about connections with people. Now, the debt becomes political, the obligation becomes for Katniss to make a statement, to defy the Capitol.

Katniss memorializes Rue in a bed of flowers, an act of humanity. Now her actions are conscious: she repeats the three-finger solidarity salute from District 12. It’s a clear demonstration of defiance: if the Capitol doesn’t own her, maybe it doesn’t own the districts either…

In the film, we cut to a seemingly spontaneous uprising in District 11. The workers destroy machinery and sacks of crops. Peacekeepers rush to snuff out the spark of revolt. But something has started, something that can’t be unseen.

Katniss would like to be totally self-reliant; she thinks this is crucial to survival under the system. But she can’t be, and The Hunger Games is partly the story of how she comes to realize the importance of her interdependence with others. Survival, let alone social change, can’t be individual, it has to be collective. It can only happen together.

Such small acts of kindness might seem inconsequential, but they can be the seeds of change. In our political climate, which increasingly rests on the idea that empathy is impossible, kindness might not be a distraction from radical change. Maybe it is radical change – or at least the beginning of it, as the spreading ripples of cooperation and compassion played out in the Arena, and subsequently beyond, suggest.

In The Hunger Games, a revolution emerges – or had it been planned for some time? My new book, Stay Alive, ends by examining the nature of this revolution and its implications for dissent in our own world – what it suggests about how regimes fall, and most importantly how revolutions need to be based firmly in justice if they stand any hope of creating a truly just society.

Some commentators suggest the ending of the series is essentially anti-political. The new Panem is no utopia. In the longer-term it may not even survive as a free and fair society. Katniss seemingly withdrawing from it, at least from its political life. Not continuing to fight for justice, isn’t this what the Capitol would have wanted? What kind of journey has she been on, if she ends up here?

But as I write in the book, there’s another interpretation. Katniss not only survived the Hunger Games, she did it through collaboration and compassion. And ultimately, faced with a difficult choice, she stood against hierarchy and exploitation in all its forms, and paid the price. Now, understandably, she hopes for healing.

What Katniss really represents is a hidden revolution – a kind of revolution that we don’t have to wait for, one that we can start to live every day, starting now.

But for more about that, you’ll have to buy the book.

Stay Alive: Surviving Capitalism’s Coming Hunger Games is published in April/May 2021 by Zero Books and can be pre-ordered from the following places now:

10 ways The Hunger Games is our present – and our future. #9: “They’re afraid of you”

How regimes try to contain young people

How regimes try to contain young people

This is a series of blog posts based on my new book, Stay Alive: Surviving Capitalism’s Coming Hunger Games, published in April/May 2021 by Zero Books.

Brutal competition, the stark division between winners and losers, constant surveillance, the pressure of perfomative living, the fear that life might be over before it’s really begun...of course The Hunger Games speaks to young people. In its dramatization of ordinary young heroes fighting for their lives, and to retain their dignity and integrity, they see their own world and who they might have to be in it.

The Capitol and its commentators want them to submit to its propaganda, to doubt their own senses, and to blame themselves for failing to fit into its fraudulent constructions. But the reality of the system is revealed in what they feel and experience: fear, anxiety, trauma, alienation, hopelessness.

But why does the Capitol go to all of this trouble to treat ‘its’ young people so horrendously, at the risk of generating widespread disgust at its rule? The answer is because its fear of them is even greater.

Which is why The Hunger Games is about containment, and the fundamental fear that Capitol elites have about the people of the districts. Katniss, the other tributes, the districts, even the victors – all are constantly contained and herded, by fences, borders, Peacekeepers, artificial arenas and deadly hazards, pervasive propaganda and reality TV productions.

In our world, young people will live in a future of walls, of containment driven by collapse, environmental destruction, scarcity and a sociopathic elder elite’s fear of losing power. More than three decades after the fall of the Berlin Wall, young people are unconstrained by fears of authoritarian ‘socialism.’ New walls need to be constructed, of individualism, intolerance, hopelessness and passivity. Working out what’s real and what’s Capitol propaganda will be crucial, the first step to surviving the coming hunger games. And let’s remember that the Capitol wouldn’t bother with its propaganda if it wasn’t fundamentally scared of us.

In The Hunger Games, Katniss is the last person to recognize her significance, and our potential to bring down the walls. Despite starting the story in numbness and self-doubt, Katniss will come to recognize she’s not to blame, that it’s the system, and that recovery and healing, personal and collective, will only be possible if the true source of terror is confronted.

But the Capitol and the rebels identify her power long before she does. What she wakes up to is not the full horror of the system, she’s more than aware of that. No, what she comes to understand is that, in the world of Panem, survival is unavoidably a revolutionary act.

The Capitol tries to contain its children because it’s terrified of them politically, because despite its propaganda, there’s nothing natural or inevitable about the state it’s created and coerces people into accepting. Its fear of youth is really its fear of how they could challenge its institutions of exploitation. In Panem, the Games are a pre-emptive punishment against young people’s revolutionary potential.

What The Hunger Games points to, an important part of its success with young readers, is its examination of how youth oppression is so normalized that we often don’t notice it.

Adults should protect young people, not punish them. But protective adults are too often absent. The activist and organizer Andrew Slack has noted the prevalence of “orphans versus empires” in much popular fantasy, from Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz, and Superman and many other superheroes, to Harry Potter. As Andrew suggests, this isn’t a coincidence.

Orphanhood is also reflected in The Hunger Games. Katniss and her sister Prim have lost their father and effectively their mother as well. Katniss is angry about her mother’s resignation, even though she can understand it. Like many children from dysfunctional homes, Katniss keeps their situation secret from the outside world, out of fear of the authorities taking her and her sister away into ‘care.’ The other young people don’t really seem to have present parents either. And then, being taken from their homes and forced to fight in the Games represents the ultimate orphanhood.

But politically as well, as young people push further into the world, they discover another orphanhood. There is no real adult leadership, responsibility or nurturing in Panem. And not enough in our world either. Young people are orphans of a system that has abandoned them, and humanity. Like Katniss, they’re a generation left to figure it out for themselves.

Oh, and it turns out that the elders in the Capitol are right to fear the young people of Panem.

In our world, as conditions worsen, there will probably be some kind of generational rebellion. Frustrated by the lack of response to crisis, some young people will become more militant, even take violent action against a system that’s doomed them. But like the first rebellion in The Hunger Games, against the overwhelming power of the Capitol this is likely to fail. Violent protest will be used to justify state repression, and then we’re heading into the hunger games.

So whether we read The Hunger Games in generational, geographical, historical, colonial, economic, environmental or class terms, it depicts our most likely endgame. Propaganda about freedom and free markets will be replaced by calls for security for a few and serfdom for many. The Capitol will openly serve corporate interests against workers. Control will be achieved through state repression and economic segregation, an authoritarian capitalism. These regimes will favor older people and contain and immiserate the young. The serfs will be heavily policed and militarized, aided by advanced technology and near-total surveillance, a digitized dictatorship. Media spectacle and shock tactics – perhaps some future version of the Hunger Games, probably a punishment for ‘political dissidents’ – will be used to deter popular resistance.

For the masses, the system will induce exhaustion and a focus on survival. A minimal meritocracy will buy-off a small part of the non-elite, but in reality social advancement will be severely limited. This new order will not be popular, but it will be justified as necessary to preserve society against ‘hostile forces.’ This system needs a name. After The Hunger Games, we could call it ‘capitolism’.

Stay Alive: Surviving Capitalism’s Coming Hunger Games is published in April/May 2021 by Zero Books and can be pre-ordered from the following places now:

10 ways The Hunger Games is our present – and our future. #8: “It’s all a big show. It’s all how you’re perceived”

How elites try to manipulate reality – and how we feel about ourselves

How elites try to manipulate reality – and how we feel about ourselves

This is a series of blog posts based on my new book, Stay Alive: Surviving Capitalism’s Coming Hunger Games, published in April/May 2021 by Zero Books.

Suzanne Collins has stated:

“Bread crops up a lot in The Hunger Games. It’s the main food source in the districts, as it was for many people historically... But there’s a dark side to bread, too. When [Head Gamemaker] Plutarch Heavensbee references it, he’s talking about Panem et Circenses, Bread and Circuses, where food and entertainment lull people into relinquishing their political power. Bread can contribute to life or death in The Hunger Games.”

‘Bread and circuses’ refers to the Roman Caesars’ strategy of quelling public discontent by providing people with food and entertainment. (Of course, the Capitol doesn’t really provide the bread; even the name of the country is a lie.) The phrase was coined by the Roman satirist Juvenal, describing how the state pacified its subjects by distracting them from political reality. The entertainment was largely provided by gladiatorial games.

In The Hunger Games novels and films, these contests are crossed with reality television techniques to create Panem’s Hunger Games. The setting draws a link between Ancient Rome and the present-day United States, with the almost limitless distractions provided by the latter’s media entertainment complex taking the role of the gladiatorial games.

We’ve already noted some of the reasons that The Hunger Games was a generational phenomenon. Another reason is this manufacture of images and storylines. Through Katniss’s experience, we see how the regime creates and manipulates these for its own ends.

By design, the Hunger Games commodify the competitors, turning them into objects, always a precondition for abuse and exploitation, so that the audience can be entertained rather than horrified by their suffering.

Leading up to the Games, the tributes are expected to act cheerfully and hide how afraid they are. Katniss and Peeta and all of the other tributes are taken to the ‘Remake Center.’ Katniss is literally scrubbed clean of the scars of her life in District 12. They’re styled for a grand parade, then have to pitch themselves on a confessional-style talk show. Each tribute is treated as a character, distinct from the human being who is about to kill or, more likely, be killed. The audience doesn’t experience them as real people, which might induce empathy with their plight.

Katniss even has to pretend she’s humbled, awed, to be in the Games, “this little girl from District Twelve.” And then in the arena, the competitors have to consider how to solicit crucial supplies from rich ‘sponsors’ in the Capitol (as her Games mentor Haymitch advises Katniss, “You really wanna know how to stay alive? You get people to like you”). Just before being thrown into the arena, the tributes are given a rating by the Gamemakers based on their chances of survival, which is important to attracting sponsors. Obviously, because no one wants to back a loser.

Suzanne Collins’ most obvious inspiration was reality TV. She’s explained that: “I was channel surfing between reality TV programing and actual war coverage when Katniss’s story came to me. One night I’m sitting there flipping around and on one channel there’s a group of young people competing for, I don’t know, money maybe? And on the next there’s a group of young people fighting an actual war. And I was tired, and the lines began to blur in this very unsettling way...”

The titles alone of well-known programs indicate the ‘values’ they promote: Big Brother, Survivor, American Gladiators, Fear Factor, Naked and Afraid... Critics have suggested how reality TV combines neoliberal ideology (competition, individualism, the offer of instant wealth, the humiliating ‘elimination’ of losers) with the normalization of a surveillance society.

In the story, the Hunger Games aren’t designed as a distraction, then. They perform a propaganda role in establishing a dominant set of social values, values that legitimize the state’s brutality and enforced inequality, and corrode the natural social solidarity that might threaten the Capitol. The Games model and promote, attempt to naturalize, the Capitol’s broader ideology: brutal competitive individualism for the masses, eternal punishment for the poor, and a hopelessness that they can ever really win.

Collins also captures how contemporary capitalism creates pressure for young people to commodify themselves, to craft a personal brand, perform, and promote their ‘best’ identity. Of course, social media provides the perfect vehicle for this. As Jia Tolento argues in Trick Mirror, these platforms are all about commodifying selfhood, but are leading us to mass alienation. Social media offers a kind of ameliorative solidarity which isn’t real; we gravitate to social media in order to feel more connected, but often feel more isolated (in a later post, we’ll consider actual solidarity). It’s just one respect in which The Hunger Games is less sci-fi dystopia than current critique.

Later, in Mockingjay, the third part of the series, Katniss is used as a symbol by the revolution, but she’s equally deeply conflicted about adopting this persona, both about her ability to play the role effectively, and the consequences of the conflict with the Capitol. It takes Katniss a long time to recognize that her power actually lies in her fragility, vulnerability and flaws – in her humanity (“The damage, the fatigue, the imperfections. That’s how they recognize me, why I belong to them”).

But perhaps the most insidious, often invisible erosion of the self derives from the daily grinding focus on survival, a kind of identity theft by a cruel, corrupt society. Katniss’ struggle will be to recognize who she really is, something that totalitarian regimes never encourage, since the beginning of the true self is often the beginning of the end of tyranny.

And indeed, Panem’s total surveillance society will come to be turned back on the Capitol. Katniss’ actions during the Games, which are not purposefully revolutionary, at least consciously, will play out in the most public way possible. The TV spectacle of the Games is a national focal point (viewing is mandatory for all of Panem’s subjects), but this is also what creates such a perfect platform for their subversion.

The Mockingjay revolution starts here.

Stay Alive: Surviving Capitalism’s Coming Hunger Games is published in April/May 2021 by Zero Books and can be pre-ordered from the following places now:

10 ways The Hunger Games is our present – and our future. #7: “I’ve never been a contender in these Games anyway”

The games the Capitol makes us play are not natural at all

The games the Capitol makes us play are not natural at all

This is a series of blog posts based on my new book, Stay Alive: Surviving Capitalism’s Coming Hunger Games, published in April/May 2021 by Zero Books.

The Hunger Games are a televised gladiatorial combat event in which 24 teenagers, called tributes, are forced to fight to the death in a deadly, natural-looking but actually artificial arena. The winning tribute and their home district are rewarded with food and riches. The Games provide entertainment for the Capitol. Most importantly, they remind the districts of its overwhelming power.

Panem’s rulers present the Games as a celebration, and also perversely an unending punishment for the districts’ past rebellion. But the Games embody the Capitol’s ideology in a deeper way. They normalize a destructive set of social ‘values’ which serve the elite, namely brutal competitive individualism among the poor. This is really why the Games are so important to the Capitol.

The Games promote a brutal competitive individualism that seeks to obliterate all other values, and humanity itself. They exert the Capitol’s control beyond its economic exploitation of the districts, into peoples’ ability to envision an alternative future free of domination.

But the Games also have another role: promoting the illusion of meritocracy. In the film adaptation of the first book, President Snow explains to Seneca the Gamemaker the reason for the Hunger Games. He could easily pick 24 children from the districts and shoot them, but the important thing is to have a winner. This gives people a glimmer of hope: “A little hope is fine. A lot of hope is dangerous. A spark is fine, as long as it’s contained.”

Suzanne Collins suggests how the system manages dissent through this modicum of meritocracy. The economy offers no possibility of advancement, but through the Games there’s the promise to the victors of a life of luxury and the adulation of the Capitol. Of course, it’s a small chance, first to be chosen for and then to survive the tournament. But while the Games strike terror in the poorer districts, competing in them is something that some young people in the career districts actually hunger for.

The Capitol’s presentation of the Games – two young tributes from each district “to be trained in the art of survival and to be prepared to fight to the death” – is of course deceptive. The environment of the arena provides the illusion of choice: competitors can adopt different strategies and use whatever skills they like. They could even make the ‘choice’ not to kill. But as noted, its meritocracy is a myth, since the career tributes typically win, and sponsors typically favor those most likely to prevail. The game is rigged against the poorest districts from the start.

It’s frequently forgotten that the term ‘meritocracy’ was not meant to be taken literally. It was coined in 1958 by the sociologist Michael Young in his essay The Rise of the Meritocracy as a satire of the seemingly merit-based education system in the UK at the time. Young claimed that this system only appeared to reward the intelligent and hard-working; in reality its testing masked a selection process that served the already privileged, rather like the pre-Games judges’ scoring system in The Hunger Games that favors the career tributes who have been training from a young age. Even if a few can climb into privilege, this doesn’t justify the wealth of the Capitol. In a deeply unjust system, meritocracy is a myth. The odds are never in our favor.

This meritocracy serves another purpose. In theory at least, the Games are every man and woman (child, really) for themselves (the supposedly natural elite of the Capitol never puts up its own competitors). But the objective is to crush feelings of solidarity and interdependence between the districts, which is to say, the ordinary working and middle class (such as they are) of Panem. Much as how modern states use class, religious, ethnic and other differences to divide the working class and hinder their organization, Panem uses the Games to foster competition rather than cooperation between the districts, despite the fact that they have more in common with each other than anyone inside the Capitol’s citadel. They literally get the districts to fight against each other.

At first sight Panem may not resemble a ‘free market,’ but there are more similarities between the two than we might think. The Games particularly model capitalist competition. We’re compelled to see others as tributes. There are limited resources – artificially limited, in turns out, to force us to fight each other.