Why write about The Hunger Games?

I didn’t expect to write about The Hunger Games. Just like my book on Star Wars (or rather, today’s politics as interpreted through the world’s most popular space saga), I like and admire Suzanne Collins’ story of a dystopian regime and the revolt against it. But in neither case could I call myself a superfan.

When The Hunger Games began in 2008, many commentators lumped it in with other young adult genre fiction such as Twilight and Divergent. But The Hunger Games is political, and it’s since become a defining story for a generation that’s grown up with economic crisis and never-ending war. It’s about an elder elite that uses state power, a compliant media, and violent spectacle to pacify its population. It’s about how a rebellion is sparked by defiance and spreads through subversive symbols, while the regime responds in the only way it knows.

In Panem, the post-disaster United States setting of the series, an uber-rich ruling class gorge themselves in their gleaming high-tech Capitol, while working people are left behind to survive in exploited districts. Revolution is a forgotten hope kept at bay by brutal policing, aching poverty, and rigid class segregation. And yet…

The year 2019, when I started the book, saw youth-led revolts in many countries around the world, from Hong Kong to Chile, Thailand to Columbia. Despite different local flashpoints, underlying all of them were extreme inequalities which especially disadvantage young people, and the willingness of elites to crush any challenges to their power. The world hadn’t seen a wave of street protests like this since the late 1980s, surpassing the scale of the Arab Spring protests of the early 2010s.

The Hunger Games generation, if we can call them that, are the tributes thrown into an arena of increasingly brutal competition from which it seems like there’s no escape, their futures sacrificed for a greedy, corrupt elder elite. No wonder the series still resonates with young people today.

Not coincidentally, a number of these protests also used imagery and slogans from The Hunger Games. In an important sense, the series predicts how regimes around the world are likely to respond to increasing youth-led protests against their power. And with the climate crisis and environmental disaster, the series is about a coming future of enforced scarcity and segregation, and an emerging form of authoritarian statism I call in the book ‘Capitolism’.

It’s the story of our times, and most likely of our future as well.

As I discuss in my book, called Stay Alive (those who have read the books or seen the films will get the reference), The Hunger Games is about how regimes fall, but how the revolution against power and exploitation can never end. It’s about collapse, war, rebellion, trauma, and recovery. It’s dark, emotionally and politically truthful, and while it doesn’t flinch from the horrors of its setting, it’s also ultimately, eventually, realistically hopeful.

The real hunger games are just beginning. But so is the struggle against the Capitol. We need to return to Panem.

That’s why I’ve written about The Hunger Games.

Stay Alive: Surviving Capitalism’s Coming Hunger Games, will be published in April/May 2021. Here’s where you can pre-order the book.

How Star Wars can help today's young rebels save the future

How Star Wars can help today's young rebels save the future - here’s a quick slideshow summary of my forthcoming book Welcome to the Rebellion, coming to your galaxy this summer.

How Star Wars can help today's young rebels save the future - here’s a quick slideshow summary of my forthcoming book Welcome to the Rebellion, coming to your galaxy this summer. (Click on each picture to advance to the next slide.)

Why the politics of Star Wars still matters (part 10): “Rebellions are built on hope”

This is a series of posts drawing on my forthcoming book Welcome to the Rebellion: A New Hope in Radical Politics (published in June 2020 by Zero Books).

This final post is about hope, a new hope.

This doesn’t feel like a hopeful age. Today’s young people have grown up with crisis: financial crashes, terror attacks, political instability, rising xenophobia and authoritarianism. The Star Wars prequels anticipate this era of threats and fears, manipulation and misinformation, militarization and creeping restrictions on civil liberties. To Dave Schilling, the understandable pessimism felt by some young people is also evident in the most recent Star Wars films:

“People my age, the dreaded “‘90s kids” who grew up with the worst Star Wars movies – the cursed prequels – look back at the promise of post-war America with a mixture of contempt and jealousy. You promised us a better tomorrow and we got terrorism, massive income inequality, the threat of nuclear war, political instability throughout the globe, and whatever devastation climate change will bring. Similarly, Luke, Leia, Han, and the Rebel Alliance promised a new Republic and a return to decency in the galaxy... Our new characters, particularly Rey and Kylo Ren, find themselves questioning the value of all that hope.”

Empire controls the economic system, financial institutions, governments, the most powerful media. It has police forces and armies, courts and prisons. If empire has this much power, what chance do we have? And yet, contrary to the pessimism of capitalist realism – the pervasive sense that there is no alternative – empire may be surprisingly precarious. As discussed in a previous post, empire is facing a set of interlocking economic, ecological and energy crises. Massive inequalities spur resistances from below, some reactionary and regressive, but others, like the global justice and ecological movement, offering the potential of a just and free alternative.

Given its fundamental weaknesses, it’s unsurprising that Palpatine’s dictatorship only lasts for 22 years, less than a human generation. Empires that provide people with little hope, and little hope for change, are doomed. Our empire has its own weaknesses. It might seem all-encompassing. But its exceptional claim to universalism, that there is no alternative, is actually its greatest vulnerability. If this is the only system there is, we demand that it should be better, fairer, more just. And when it can’t be, because it is fundamentally unjust and exploitative, and when it embraces authoritarianism in response to rising public anger, it gives too many people too little hope for change...

If we feel hopeless, it’s because we forget that we are more powerful than we can possibly imagine. As Rebecca Solnit puts it in Hope in the Dark, we are a superpower whose nonviolent means are more powerful than regimes and armies. Empire knows this, just as in The Empire Strikes Back the Emperor warns Darth Vader that Luke “could destroy us.” This is why mainstream media suggests that popular resistance is ridiculous, pointless or criminal (unless it’s far far away, or a long time ago). This deliberately obscures the numerous nonviolent, direct action successes that are hidden in plain sight. We need to remind each other of the history of victories and transformations that could give us the confidence that we can change the world, because we have so many times before.

Whatever you think about Star Wars, many people find it inspiring and enjoy losing (or often, finding) themselves in its worlds and characters. They love the bravery and camaraderie of its heroes, and love to hate the nihilism and barbarity of its villains. If capitalist realism is about the perpetual present, if it tries to convince us that nothing can ever change, perhaps the longevity of stories such as Star Wars signifies the persistence of our belief in the possibility of a different world.

A whole series of books couldn’t do justice to all of the individuals, groups, communities and campaigns that are now rising up. The new new left, the young left (does it really matter whether we label them as ‘left’ at all?) aren’t listening to the pessimism and passivity of some of their elders. Nor do they fall for the lies of empire. To paraphrase Emma González, one of the leaders of the #NeverAgain gun control movement, this is a ‘no BS’ generation of activists and campaigners.

There are many ways to connect these diverse movements: as mass mobilizations against violence and oppression, in their recognition of the systemic nature of what we’re up against, and by their refusal to accept so-called pragmatism and political realities. But they’re also about freedom, not some abstract notion but real freedom – from the exploitation of land and environment, police brutality and institutional injustice, to being afraid of being killed at school and of the climate chaos that’s coming our way. Just like our favorite fictional rebellion, they fight for the freedom necessary for survival.

As the stories told by elites crumble, these movements are contesting the old common sense and creating new ones. Telling a different story is vital to winning change and recruiting new rebels. The previous forms of solidarity on the left, most obviously trade unions, have been significantly eroded, deliberately so by the forces of empire. In the era of globalization, the absence of structures of solidarity leaves those left out susceptible to the exclusionary identities and fake solidarity of right-wing populist appeals, or even worse. We need to build a better, more appealing common identity for change. We need a rebel alliance.

Some may disagree, but Star Wars has always been political, and the saga will always be with us as long as there is oppression to be overturned and rebels who dream of doing it. As a fantasy, it connects with what is arguably the most real thing of all: the need to stand against domination and to fight for a better world.

As the anti-racism activist Chris Crass has said, we need to avoid being unconscious stormtroopers of death culture, helping imperial forces perpetuate systems of oppression. Instead, our calling is to see empire all around us, and to join a rebel alliance of others who are working to build a future of collective liberation and justice for all. As Luke says to Han: “Why don’t you take a look around. You know what’s about to happen, what they’re up against. They could use a good pilot like you, you’re turning your back on them.”

The hero in us heeds the call to adventure. To live a life of fantasy today is not to escape into our favorite sci-fi films, so much as it is to believe that we can somehow escape from what empire is and what it is doing to our fellow human beings, to our planet and to ourselves. But there is still time, just about. Together, we can fulfill our destiny and become the guardians of peace and justice in our galaxy. Looking inside ourselves, we know we have already made our choice.

Welcome to the rebellion.

Welcome to the Rebellion: A New Hope in Radical Politics, will be published in June 2020 by Zero Books. You can pre-order your copy now at:

US: Amazon.com, Barnes and Noble, Books-A-Million, Indiebound

UK: Amazon.co.uk, Zero Books, Waterstones, Foyles, Blackwells

Rest of the world: Chapters/Indigo, Booktopia, Book Depository, Goodreads

A FREE preview of the introduction to the book is available on Amazon.

Why the politics of Star Wars still matters (part 9): “That’s how we’re gonna win. Not fighting what we hate, but saving what we love”

This is a series of posts drawing on my forthcoming book Welcome to the Rebellion: A New Hope in Radical Politics (published in June 2020 by Zero Books).

In the previous post I focused on the need for a broad, popular resistance to empire. But this can’t just be negative.

In Star Wars, we know what they were against, but what were the Rebels for? Their proper name was actually the Alliance to Restore the Republic. As their Formal Declaration of Rebellion suggests, the Rebellion is largely reactive, a list of grievances against the Emperor and his Empire. Albeit that these grievances contain the seeds of freedom and democracy, there’s no apparent plan to bring greater justice to the galaxy. Is this why the Rebellion seems to lack popular support?

The Alliance’s mission was to restore hope against an Empire that wants to crush dreams. Important though this is, our rebellion requires more. We need to tell a story about the corruption and crimes of empire, but also paint a picture about a better future, one that gives people hope.

Even if we wanted to, we can’t just promise a return to the republic we’ve lost. In contrast to 1990s’ talk of a coming ‘progressive century’, the decade since the global financial crisis has all but destroyed so-called centrism. Centre-left parties have suffered defeats in almost all Western democracies.

Forced to choose sides by the crisis, the centre-left struggled to tell a new story. Like the Jedi during the Separatist crisis (which eventually leads to Palpatine’s coup and the domination of the Empire), centre-left parties were seen by many voters as part of the self-interested elites who caused the crash. Right-wing authoritarian populists gladly seized their chance, with simple stories about immigration, jobs, elite corruption, the iniquities of globalization and the loss of control to phantom menaces such as the European Union or the United Nations.

The centre-left was vulnerable because it had embraced a technocratic liberalism which largely accepted the assumptions of the new right’s empire of markets. They said, we can manage the system, but in a fairer way. They didn’t seem to recognize the dark forces that were on the move: widening inequality, the increasing power of the hyper-rich and the fracturing of republics into winners and losers from globalization.

We need to offer a new republic. Our rebellion is for justice and freedom. Indeed, freedom has always been what radical democratic left politics has been about – from fighting against segregation and for women’s suffrage, to workplace representation, the minimum wage, social security and healthcare. These struggles have also been battles about the definition of freedom and who is granted it.

Now, the left needs to take freedom further, taking on concentrations of power such as monopolistic companies that seek to dominate the economy, degrade the environment and weaken the power of consumers, workers, voters and communities.

Fortunately, anti-empire rebellions are everywhere bubbling below the surface, and increasingly above it. The real impulse of resistance is coming from the anarchist, autonomist and anti-authoritarian left. Old-school communist revivalists suggest that these movements represent ‘revolt without revolution’, and criticize brave rebels as obstacles to a ‘proper confrontation’ with the ongoing crisis of our economic system. Instead, they argue that we should wait patiently for the Big Future Event, the cataclysmic act of upheaval that will give birth to the glorious new world. As K-2SO from Rogue One would say, “I find that answer vague and unconvincing.”

The ultimate freedom is the freedom to choose political alternatives, which empire has sought to deny. Rather than holding onto ancient lore about the coming socialist utopia, the best way to resist the lure of fascism is to live its opposite. Why would we want to replace one empire with another? To build a rebel alliance, the left needs to be expansionary and welcoming, continually extending rights and recognizing new voices. This isn’t a distraction from the rebellion, it is the rebellion.

At the same time, while we need to look forward, part of our story involves looking back. Not to some utopia that (equally) never existed, but to remind us what is possible – the old republic wasn’t all bad – and what empire has taken away.

In the first post in this series, I talked about the importance of storytelling in politics. One of the things I suggested is that the left can be bad at stories because, being forward-looking in wanting to build a better world, it can recoil from the notion of restoring balance that is so often essential to dramatic storytelling. The left is much more likely to argue (correctly) that the golden age never really existed, that many nations were founded in violence and exclusion, that there is no past to which we should want to return. The radical struggle has always been to include more people in society, not to re-establish rule by the few.

The influence of mythologist Joseph Campbell on Star Wars has been somewhat overstated, but his codification of world myths contains some useful insights for the stories we need to be telling. Campbell divided his monomyth into three main stages: Departure, Initiation and Return. Rebels are forced to ‘leave home’ to restore balance to the world. In Campbell’s terms, destroying the Death Star is the ‘world-restoring task’. But this doesn’t allow the hero to return to the past, since it doesn’t exist anymore. The world is renewed, but it has also changed irrevocably. And so, saving what we love isn’t backwards looking; it means accepting that a new world will be born.

For example, in Climate, A New Story, Charles Eisenstein proposes a change in the story used by the climate justice movement. Rather than focusing on rising carbon emissions or the economic value of ecosystems, Eisenstein suggests that environmentalists tell a much more emotional story about a love of nature, about protection and loss. Instead of impending catastrophe, we need to cultivate meaningful emotional and psychological connections which form the foundation for real, actionable steps to care for the planet.

The dark side longs for a past in which power was held by a few, and people and the environment could be plundered at will. The light side really is love – love for what was good in the past, for what can be saved, but also for what could be to come.

In the final post in this series, I’ll discuss the importance of hope.

Welcome to the Rebellion: A New Hope in Radical Politics, will be published in June 2020 by Zero Books. You can pre-order your copy now at:

US: Amazon.com, Barnes and Noble, Books-A-Million, Indiebound

UK: Amazon.co.uk, Zero Books, Waterstones, Foyles, Blackwells

Rest of the world: Chapters/Indigo, Booktopia, Book Depository, Goodreads

A FREE preview of the introduction to the book is available on Amazon.

Why the politics of Star Wars still matters (part 8): “It’s just… people”

This is a series of posts drawing on my forthcoming book Welcome to the Rebellion: A New Hope in Radical Politics (published in June 2020 by Zero Books).

This series started in the argument that the left needs to own rebel stories if it’s going to win popular support and battle the authoritarian populists who have been in the ascendancy around the world.

As stated in The Rise of Skywalker, the way the Empire/First Order/Final Order wins is by convincing people that they’re alone, that they’re the ‘only’ ones who hate imperialism and exploitation and want real and radical change. For me, the best moment in the film is during the climactic space battle around Exegol. The small Rebel fleet is being decimated by the Final Order. The Rebels had previously called on the rest of the galaxy for help, but no-one came. However, at the last moment, thousands of ships appear. The galaxy has decided it’s sick of empire and is ready to fight back. The Order’s General Pryde asks for a report on the Rebel navy, but a junior officer replies, “That’s not a navy sir. It’s just… people.”

In general, Star Wars plays out the tension between the need for a so-called revolutionary vanguard and the importance of mass resistance, especially in its more recent films. For much of the saga, the Rebels seem more vanguardist. We follow a core group of heroes, and mostly only see a small Rebel Alliance. But that’s changed.

I noted in a previous post the much more political and divisive recent ‘debate’ over Star Wars, and how this really took-off with The Last Jedi. Perhaps the reason is that anti-elitism runs through that film, echoing the critiques of the previous films made by the science fiction writer David Brin and others, that the saga has been elitist in its focus on the special, ‘royal’ Skywalker lineage. Brin argues that from The Return of the Jedi onwards and especially the prequels, Star Wars reflects the great man theory of history, especially in the notion that (Jedi) elites have an inherent right to arbitrary rule.

But The Last Jedi challenges all this. Its anti-elitist theme and its democratizing of the Force suggest that rebellions against overwhelmingly more powerful forces can’t depend on the heroics of the few. Even then, at the end of the film, the depleted Resistance calls for help from the rest of the galaxy, but they’re ignored. Perhaps the Rebels are paying the price for their failure to build popular support – and to tell the right stories to generate that support. (It’s this scenario that’s repeated at the end of The Rise of Skywalker, but as noted, with a very different, much more hopeful outcome.)

What this reflects is that our assumptions about (radical) leadership are changing. The new awakening of youth-led protest groups and campaigners reject hierarchy, both in how they organize and in the world they want to see. Going back to stories, this reflects a broader shift reflected in popular culture. Jeff Gomez, a writer and transmedia producer in fantasy, science fiction and young adult genres, has written about how we are shifting from the hero’s journey to a collective journey, to ensemble-based narratives with multiple protagonists, missions and ways of succeeding.

In our deliberately depoliticizing society, many people find politics boring and divisive. But a collective journey story offers far more potential for engaging them. Collective stories (Gomez also uses The Last Jedi as an example) tell us that headstrong masculinity is over; contrast this with the right’s savior worship and some of the twentieth century’s most destructive ‘stories’, built as they were around the myth of the great leader. Our new stories are about communities, intersectional coalitions for action, struggling to achieve systemic change through the power of their differences but drawn together by universal values. Together, we must become our own salvation.

That requires new thinking. In The Last Jedi, a grizzled Luke Skywalker (hiding away like the hermits Ben Kenobi of A New Hope and Yoda of The Empire Strikes Back) denounces his old order: “[I]t’s time for the Jedi to end... the legacy of the Jedi is failure, hypocrisy, hubris.” As Toby Moses notes, the film subverts the series and hero stories generally by presenting a rebellion in which:

“[A]nybody can be a hero, so there’s no excuse not to get involved in the fight... If the original trilogy was about waiting for a hero to rescue the world from a tyrannical, authoritarian regime, and the prequels were an (albeit ham fisted) attempt to examine how democracy can easily mutate in to dictatorship... [Rian] Johnson’s entry has rooted the future of the series in a populist framework of how to defeat tyranny through community.”

Perhaps it was this that really provoked such ire among some fans and conservative commentators. The Last Jedi says we need to let yesterday die, kill it if we have to, in its challenges to saga lore and in the battle between the past and the future represented by its main protagonists Kylo Ren (angry heir to the Skywalker dynasty) and Rey (a “nobody” – or, it turns out in The Rise of Skywalker, not quite…). The hope that survives rests not in the individual hero’s journey, but in the collective, in the depleted but determined remnants of the Resistance, now the Rebellion. At one desperate moment, as Poe Dameron asks Lando Calrissian: “How did you do it? Defeat an empire with almost nothing?” Lando replies: “We had each other. That’s how we won.”

The right looks to strong leaders (“I AM the senate!” as Palpatine declares). In the rebellion, we look to us.

In the next post, I’ll discuss what the kinds of rebel stories we need to tell in order to build a broad, popular alliance against empire.

Welcome to the Rebellion: A New Hope in Radical Politics, will be published in June 2020 by Zero Books. You can pre-order your copy now at:

US: Amazon.com, Barnes and Noble, Books-A-Million, Indiebound

UK: Amazon.co.uk, Zero Books, Waterstones, Foyles, Blackwells

Rest of the world: Chapters/Indigo, Booktopia, Book Depository, Goodreads

A FREE preview of the introduction to the book is available on Amazon.

Why the politics of Star Wars still matters (part 7): “There are alternatives to fighting”

This is a series of posts drawing on my forthcoming book Welcome to the Rebellion: A New Hope in Radical Politics (published in June 2020 by Zero Books).

I’ve argued in previous posts in this series that, as illustrated through the Star Wars saga, rebel stories are crucial in today’s politics, authoritarian populists have been better at telling these stories than the left, the Death Star is a pretty good metaphor for a destructive globalized industrial capitalism, this requires us to step up to challenge Empire-like extraction and exploitation, the saga reflects a generational conflict of values that’s still relevant today, and that we need to provide a compelling alternative to the lure of the dark side of authoritarian populism.

In Star Wars, the rebels blow up the Death Star (more than once). Of course, it’s just a metaphor. But taking the question seriously, is violent resistance against empire ever justified?

Part of the argument in my book is that Star Wars reflects the politics of the 1960s new left. Perhaps the most famous declaration of new left views was the Port Huron Statement, also known as the Agenda for a Generation, a 25,700-word manifesto drafted by Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) members in June 1962. This articulated the fundamental problems of American society. It was a non-ideological call for participatory democracy (it brought the term into common parlance), as a means and an end, to be achieved through nonviolent civil disobedience.

Relatedly, John Powers interprets Star Wars as a counter to the Cold War anti-communism of politicians like Richard Nixon, who used the phantom menace of ‘leftist infiltration’ to justify the domestic control of radical political groups. George Lucas imagined a battle against a total control police state that had turned inward against its own citizens. In part because of this backlash, the new left faltered and fractured. Some splinters became violent, perhaps the inspiration of Star Wars’ warnings about being led by anger and hatred.

To Powers, the hope in Star Wars calls out to the (temporarily) lost dreams of the new left:

“With Star Wars, Lucas gave the rebels he associated himself with a single concrete victory over an easily identifiable villain (Space Nazis). These concrete villains and victories echoed the far-less concrete constellation of victories that had left youthful liberals discouraged. Perhaps Lucas’s genius was delivering a triumphant reward [that] no real-world victory had actually delivered, at a time when alienation and cynicism passed for common sense.”

Powers doesn’t say it, but Star Wars, released in the same year that punk exploded, shared some of the same militant rage against the machine. But the saga also warns against this rage.

To the famous scene in Kevin Smith’s Clerks, in which a character questions the Rebel Alliance’s attack on the second Death Star:

“A construction job of that magnitude would require a helluva lot more manpower than the Imperial army had to offer. I’ll bet there were independent contractors working on that thing: plumbers, aluminum siders, roofers... All of a sudden these left-wing militants blast you with lasers and wipe out everyone within a three-mile radius. You didn’t ask for that. You have no personal politics. You’re just trying to scrape out a living.”

Fair point. Some of today’s revolutionaries’ apparent longing for a violent transformation of society recalls the Emperor’s attempt at manipulating Luke at the end of Return of the Jedi: “Now, release your anger. Only your hatred can destroy me.” More often, the opposite is true.

Many campaigners and activists have long argued that nonviolence is more effective than violence. Others suggest there are no easy maxims and that in some situations a mixed approach may cause less suffering than a strict adherence to nonviolence.

Even if the latter is true, fascists love violence, and authorities will seek (and often invent) any justification to quash resistance. Instead, Mahatma Gandhi spoke of satyagraha as the basis for his strategic campaigns of nonviolent civil resistance – the truth force, or the power of holding on to truth. Nonviolence, or ahimsa, is less an idea than a physical reality, a force at once physical and moral, pervading the universe. It’s not really about peaceful protest, it’s about mastering your will, individually and collectively, and transforming the terms of the debate. It’s about making the situation as uncomfortable for oppressors.

If this sounds rather Jedi-like, that’s no coincidence. George Lucas was clearly influenced by Eastern philosophies in developing the idea of the Force (called the ‘Force of Others’ in early drafts of A New Hope): the dualities of light and dark, love and fear, and avoiding extremes and urging moderation in all things. And as dramatized in the films, while the energy of anger can drive us to act, it is hope and humanity that sustains rebellion and leads to victory.

While Star Wars is sometimes accused of glorifying violence as a means of political action, key moments in the films revolve around the wisdom of avoiding it. In Return of the Jedi’s final confrontation, Luke discards his weapon rather than strike down Darth Vader and succumb to the dark side. This is echoed in the climax to The Last Jedi, when Luke “confronts” Kylo Ren in order to save his friends. Risking death, Luke rejects the lure of violence and domination, and so his father’s generational values – a truly revolutionary act.

As Mark Eldridge surmises:

“Fighting when you have no other choice, to stand in defense of others, is Good; fighting from a place of anger or hatred is Bad. The ethics of Star Wars are not consequentialist – it has a strong value system and motivations are as important as results. Fighting with anger – tapping into the dark side – may yield quick, positive results, but it will come at a great cost, which will ultimately be your soul.”

In the next post, I’ll discuss what Star Wars illustrates about who leads the revolution.

Welcome to the Rebellion: A New Hope in Radical Politics, will be published in June 2020 by Zero Books. You can pre-order your copy now at:

US: Amazon.com, Barnes and Noble, Books-A-Million, Indiebound

UK: Amazon.co.uk, Zero Books, Waterstones, Foyles, Blackwells

Rest of the world: Chapters/Indigo, Booktopia, Book Depository, Goodreads

A FREE preview of the introduction to the book is available on Amazon.

Why the politics of Star Wars still matters (part 6): “Aren’t you a little short for a Stormtrooper?”

This is a series of posts drawing on my forthcoming book Welcome to the Rebellion: A New Hope in Radical Politics (published in June 2020 by Zero Books).

As noted in the previous post, Star Wars came from a specific generational perspective, but pulled off the near-miraculous trick of immediate and massive popular appeal across age groups and political viewpoints, in part because most people missed its politics and just enjoyed (or dismissed) it as a special effects space opera joyride (which it also is).

Not everyone, though. Once upon a time, the right claimed the light side of the Force for themselves. Echoing some critics on the academic left, in this reading A New Hope heralded a cultural shift that preceded the election of Margaret Thatcher in 1979 and Ronald Reagan a year later. Here was a morality tale of individuals standing up against a suffocating statist bureaucracy, and at its worst, a Stalinist war machine. Star Wars was regarded as reasserting ‘traditional values’ in an America that was becoming increasingly secular and relativistic. And Cold War warrior Reagan liked to employ simple Star Wars-like analogies, including describing the Soviet Union as an evil empire.

But over time, some conservatives have come to embrace the Empire. Since Star Wars can be used as a mirror to our own times, we might want to listen to them when they tell us who they are.

This really started to happen around the time of the Star Wars prequels, as the anti-authoritarian – but more importantly anti-corporate – politics of Lucas’s story became unavoidable and the Empire apologists revealed themselves. In 2002 for example, as Attack of the Clones hit theatres, Jonathan Last made “The Case for the Empire” in the conservative Weekly Standard. Apparently, “The deep lesson of ‘Star Wars’ is that the Empire is good.” Sure, Palpatine is a dictator, but a “relatively benign one.” Last then added: “...like Pinochet.”

Now, you can certainly put some of this kind of thing down to trolling the libs, but this wasn’t the first (or last) time the right has expressed support for General Augusto Pinochet’s 1973 military coup in Chile against a democratically elected government, and with it the oppression, torture and murder of political opponents. What they’re really defending is the neoliberal economic experiment inflicted on the country’s citizens, which produced widespread poverty and suffering.

There are plenty of other examples of the right’s flirtation with Empire. To cite just one, Donald Trump’s former adviser Steve Bannon declared that: “Darkness is good... Dick Cheney. Darth Vader. Satan. That’s power. It only helps us when [liberal critics] get it wrong. When they’re blind to who we are and what we’re doing.”

Whether by design or not, the Star Wars sequel films reflect today’s resurgent authoritarianism. J. J. Abrams, the director of The Force Awakens (and later, The Rise of Skywalker), said the concept for the First Order (the new Empire) “came out of conversations about what would have happened if the Nazis all went to Argentina but then started working together again.” Which come to think of it, kind of echoes Bannon’s plan to unite national populist conservative political movements around the world. (It turns out in The Rise of Skywalker that the new Empire is effectively the Same Old Empire, which rather reinforces Abrams’ ‘Nazis’ point.)

It’s against this real-world background that the politics of Star Wars are now much more prominent. Parts of the internet have taken against the series, urging moviegoers to #DumpStarWars because of its perceived social justice warriorship and demanding that its owners Make Star Wars Great Again (of course, it’s possible to dislike the sequels for entirely valid reasons). But perhaps what really annoys some people is that new Star Wars reflects their own journey towards the dark side.

In the sequels, the Vader cosplaying Kylo Ren is not so much seduced into the Sith as dives into the dark side in order to act out his power fantasies. No wonder the alt-right doesn’t like the new Star Wars (but then again, what did they think the previous films were about?) Ren captures their adolescent attention-seeking shock tactics perfectly. Han Solo is right when says to Ren that “[Snoke]’s only using you for your power.” Depressed, alienated, sometimes desperate young men (it is young men, typically) are being led toward fascism by facile father figures.

This is exemplified best in the prequel films, in the story of Anakin Skywalker. George Lucas is often accused of being a bad writer, but as Cass Sunstein noticed about the prequel films:

“[They] boldly don’t do as the standard movie of this kind does, focus on individuals... [I]t’s about institutions. And they have something to say about both how people go bad... especially about a little boy who loses his mother and then his loved one... And it’s the threat of loss that gets to him... And there’s something very similar that happens with the Republic. So, the institutional failure of a squabbling legislature leading to interest in a strong paternal leader – that’s mirrored in the democratic process as it is in the individual life.”

As a result of our faltering republics, we face the grave danger of more young people turning to the dark side. Star Wars has its share of characters struggling to find their identities. They’re experiencing a tumultuous galactic civil war after all, so it’s not surprising they manifest all sorts of psychological conditions. How they cope is one of the reasons the saga is compelling to so many people, especially because our rebel heroes (and we hope, ourselves) still find ways to display courage, compassion and hope. Others, however, succumb to the Sith.

In Attack of the Clones, Anakin suggests that the Galactic Senate should be made to resolve its differences by “Someone wise.” Padmé responds, “That sounds an awful lot like a dictatorship to me.” “Well, if it works...,” Anakin counters. Later, Anakin’s personal fear of loss and lack of control leaves him prey to Palpatine’s perfidious plot to plunge the galaxy into chaos and conflict.

Reviewing the film, Michael Sragow suggests that, “[A]ll along, Lucas intended to create a series that would demonstrate the seductiveness of fascism to boys like Anakin, who are disgusted with the compromises of a weak, degraded democracy, as well as depict the formation of a totalitarian style.” As Sragow notes, Anakin’s rebellion takes reactionary form: he chafes at lectures from naive do-gooders and is drawn instead toward a worldly-wise counsellor who seems to offer him a solution to his pain and confusion…

As Hannah Arendt suggested in The Origins of Totalitarianism, fascism is everywhere rooted in dehumanization, first the loss of dignity we feel ourselves by being left behind by capitalism, then our dehumanization of others in reaction. The preconditions for domination are individual isolation and loneliness. Indeed, Arendt called totalitarianism a kind of organized loneliness.

Rather than allowing more young people to slip into the waiting arms of empire, we need to provide them with a different grand narrative, one that gives their lives meaning and purpose, and most importantly, a new, positive commonality – something I’ll discuss in a later post.

Welcome to the Rebellion: A New Hope in Radical Politics, will be published in June 2020 by Zero Books. You can pre-order your copy now at:

US: Amazon.com, Barnes and Noble, Books-A-Million, Indiebound

UK: Amazon.co.uk, Zero Books, Waterstones, Foyles, Blackwells

Rest of the world: Chapters/Indigo, Booktopia, Book Depository, Goodreads

A FREE preview of the introduction to the book is available on Amazon

Why the politics of Star Wars still matters (part 5): “There has been an awakening, have you felt it?”

This is a series of posts drawing on my forthcoming book Welcome to the Rebellion: A New Hope in Radical Politics (published in June 2020 by Zero Books).

The previous post discussed how Star Wars dramatizes the decision to stand up against injustice and existential threats. This post digs into the generational conflict at the heart of the saga, and how it reflects our politics today.

In an earlier post I noted the 1960s new left roots of Star Wars. Generational division, distrust and misunderstanding was characteristic of the time. In response to ridiculous suggestions that the student protest movement was being directed by outside (communist) forces, Jack Weinberg captured its generational stance when he famously (and with deliberate provocation) declared that: “We have a saying in the movement that you can’t trust anyone over 30.”

Student-led activism came to a head in 1968. In the US, the wave of protest that had begun with the civil rights movement was reaching its height (the civil rights movement preceded the anti-Vietnam war movement but became more radical in the second half of the decade). Social movements were on the rise from West Germany and Japan, Mexico and Italy, to Canada and Denmark, Yugoslavia and the UK. The beach of alternative possible worlds was being glimpsed beneath the paving stones of a dull post-war conservatism. The French government was nearly toppled by what was then the largest general strike in world history, while the German student movement temporarily shut down Bonn. Universities were occupied. The rebellion even spread to schools.

As Richard Vinen notes, ’68 had several components: a generational rebellion of the young against the old (a distinct youth identity being a relatively new phenomenon), a political rebellion against militarism, capitalist consumerism and the power of the United States, and a cultural rebellion that revolved around lifestyle and rock music. There was also a growing international awareness, most notably of experiences of Western imperialism. Sometimes these rebellions interacted. They also challenged structures on the left, for example traditional trade unions, or patriarchy through feminism and gay liberation – revolutions within the revolution. (In reality, there was a “long ‘68” with a lasting influence, some of it still ongoing, as we’ll note in a moment.)

As previously noted, George Lucas wasn’t a new left leader, but he was immersed in its political culture. He attended USC Film School in the early 1960s and re-enrolled as a graduate student from 1967-1968. He claimed of his time at university, “I was angry at the time, getting involved in all the causes.” Like many young people, Lucas was a first-hand witness to an American civil war. Star Wars would transport this into space. A New Hope can then be read as somewhat autobiographical. As Dave Schilling puts it: “Luke Skywalker wasn’t that far removed from the Berkeley freshman getting a crash course in What’s Really Going On from his radical professors.”

One of the ironies of Star Wars is that it immediately found huge, unprecedented cross-generational success, while actually exemplifying a specific (and contentious) generational perspective. But it wasn’t just hating on the olds, rather it was characteristic of a new left suspicion of authority. Lucas’s own views of authority run through his Star Wars movies. As he’s acknowledged, “I’ve always had a basic dislike of authority figures, a fear and resentment of grown-ups,” manifested most obviously in the brooding malevolence of Darth Vader (‘dark father’, though Lucas denies this was intentional).

Generationally, then, Star Wars looks in two directions. It occupied the imaginations of the kids (like me) who would become the Gen Xers, but it was born of the rebellion of the baby boomers against their parents. As Mark Fisher notes in his influential book Capitalist Realism, the protest impulse of the 1960s posited a malevolent father who cruelly and arbitrarily denies the ‘right’ to enjoyment and hoards resources. Although Mark didn’t think much of Star Wars, the most famous revelation in cinema history dramatizes his point. When, at the end of The Empire Strikes Back, Darth Vader reveals himself as Luke’s father, the personal and the political, the man and ‘the machine’ (in 1960s protest terminology, the system), fuse into one. Fascism’s mean father figure is, it turns out, your actual father.

Uniting these themes, Michael O’Connor has tied together the generational and anti-imperialist interpretations of Star Wars:

“[T]he Empire was the older generation, the fathers who supposedly knew best. Britain had been America’s father before the Revolutionary War; now Lucas was encouraging a second rebellion. This time it was directed against the previous generation who had exploited America’s post-war power and prosperity by forcing its will on the rest of the world.”

Which leads us to today. More so perhaps than at any moment since the 1960s, a profound generational divide has emerged in Western politics (and not limited to the West either). From Occupy to the new youth-led protest movements, a generation of politically-conscious and active young people are developing their own growing global consciousness, most obviously around climate change and environmental destruction, but increasingly deeper, making links between how empire has exploited people and the planet to issues such as colonialism, racism, and exclusion.

Naturally, this generation has been subject to some of the same mischaracterizations as their 1960s predecessors, that they’re dangerously naïve, don’t understand history, are unaware of their own ‘privilege’, and even that they’re being directed by malevolent ‘outside forces’. Indeed, some of these accusations will have come from the very same boomers who once upon a time viewed their own parents’ generation as having led them to the eve of destruction. (I’ll discuss this new converging rebel alliance of young activists more in a later post.)

The relevance for today’s politics is not just this generational conflict (Star Wars is well-known for repeating itself, but so too does the history it draws on), it’s how it might be resolved. To Cass Sunstein, the first six Star Wars films are really about parents and redemption. Douglas Williams similarly suggests that: “Though there are many films about the conflict between parents and children in the 60s and 70s that present conflict... no film in the late 60s and 70s... showed a narrative of reconciliation – nor could it... But the Star Wars films do have that conflict... In these films, the child redeems the parent... and the world is healed.”

And that, really, is the task today’s young activists have set themselves.

But there wouldn’t be rebels without an empire of course. In the next post, I’ll discuss the lure of the dark side – including to some young people today.

Welcome to the Rebellion: A New Hope in Radical Politics, will be published in June 2020 by Zero Books. You can pre-order your copy now at:

US: Amazon.com, Barnes and Noble, Books-A-Million, Indiebound

UK: Amazon.co.uk, Zero Books, Waterstones, Foyles, Blackwells

Rest of the world: Chapters/Indigo, Booktopia, Book Depository, Goodreads

A FREE preview of the introduction to the book is available on Amazon.

Why the politics of Star Wars still matters (part 4): “Someone has to save our skins”

This is a series of posts drawing on my forthcoming book Welcome to the Rebellion: A New Hope in Radical Politics (published in June 2020 by Zero Books).

The previous post discussed the Death Star looming over all of us: the unsustainability of our global system of industrial capitalism, and the dark impulses that lie behind it. This post discusses how Star Wars dramatizes what we do once we recognize the true nature of the empire we’re up against.

Five years after A New Hope and two years after the darker The Empire Strikes Back, audiences were treated to another visionary depiction of the future in Blade Runner. Harrison Ford’s involvement meant that many filmgoers were expecting another rollicking sci-fi adventure. What they got, the relatively few who saw it at the time, was a dour, dank neo-noir.

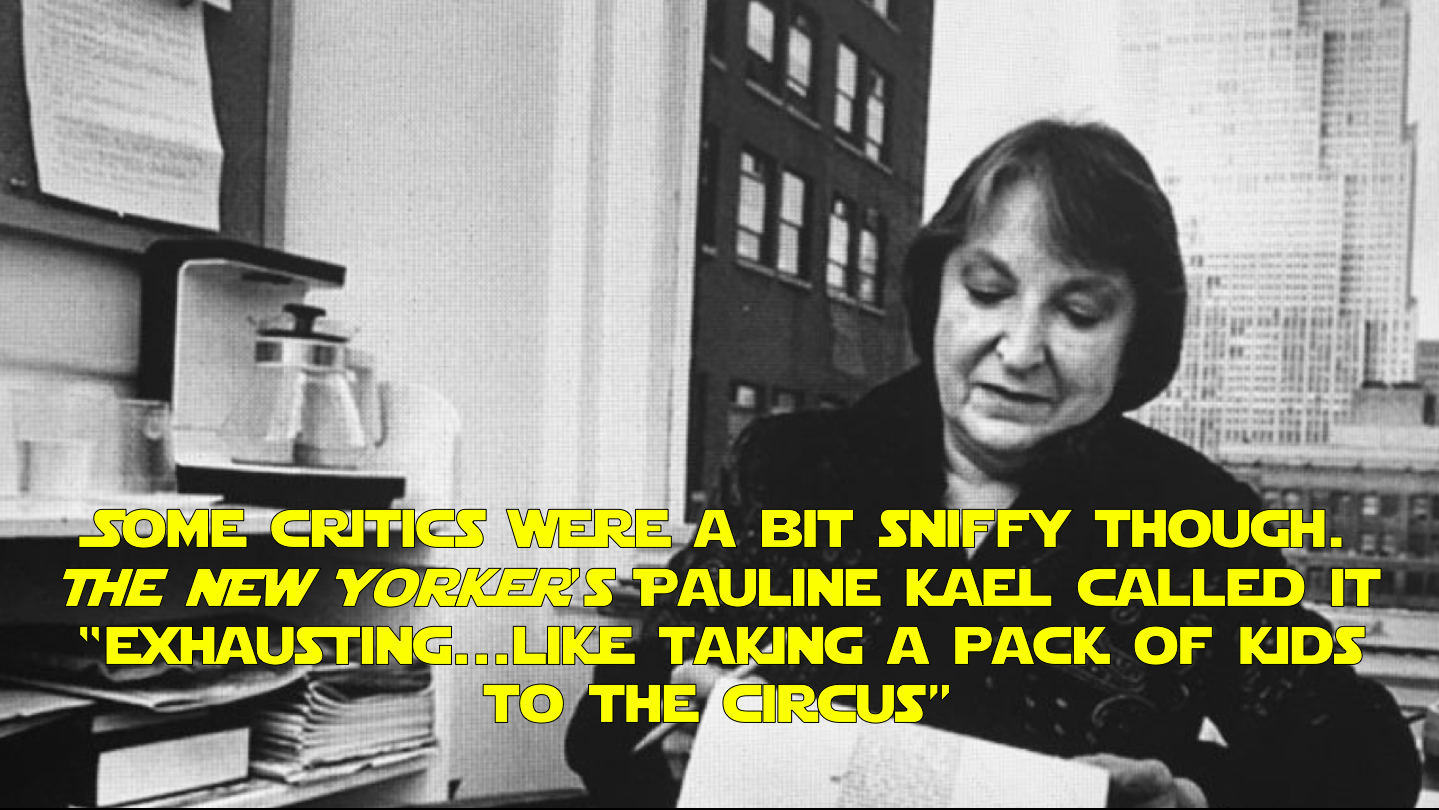

Pauline Kael, the prominent film critic of The New Yorker (professional critics were more important back then) had been dismissive about A New Hope (“exhausting …like taking a pack of kids to the circus”). But she wasn’t any happier with the considerably slower and seemingly much more adult Blade Runner either:

“[It] treats this grimy, retrograde future as a given – a foregone conclusion, which we’re not meant to question... The sci-fi movies of the past were often utopian or cautionary; this film seems indifferent, blasé... satisfied in a slightly vengeful way.”

As Kael noted, Blade Runner’s world has gone to shit, but nobody tries to change it, yet alone rebel against its towering mega-corporations (the replicant “skin jobs” do revolt, but out of a desperate desire to extend their own lifespans).

In many ways, despite its commercial failure, especially compared to Star Wars, Blade Runner has been much more influential as a template for imagining the future. Subsequently, historian Jill Lepore has identified a radical pessimism in contemporary dystopian fiction. Whereas it used to be a “fiction of resistance,” it has now become a “fiction of submission,” of helplessness and hopelessness. In contrast, Star Wars, which is deeply unfashionable in cultural theory compared to Blade Runner, doesn’t just depict a dystopian future but focuses on fighting it. It says that another galaxy is possible – if we want it.

This agency, our ability to choose a different future, is what Cass Sunstein, a leading constitutional scholar, thinks Star Wars is all about, our ability to make the right decision when it really matters. Sunstein, who among other things pioneered the study of ‘choice architecture’, emphasizes that the main characters in Star Wars are resolutely active:

“Star Wars also makes a bold claim about freedom of choice. Whenever people find themselves in trouble, or at some kind of crossroads, the series proclaims: You are free to choose... the foundation of its rousing tribute to human freedom.”

In Star Wars, the new hope lies in young people. Luke is described as being 18 years old in the script. Leia might be 19, but she’s maybe the most important rebel in the galaxy. From the first time we meet her, she refuses to be intimidated by Darth Vader and the Empire’s extensive apparatus of fear. And after the Empire comes for Luke (or rather, the droids that have come into his possession carrying the plans for a new super weapon), he doesn’t hesitate. Indeed, rebellion seems like a liberation to him. It’s also worth noting that, given their age, these young people had never known anything but the Empire, and yet they envisage its overthrow.

As George Lucas reflected: “One day Princess Leia and her friends woke up and said, ‘This isn’t the Republic anymore, it’s the Empire. We are the bad guys. Well, we don’t agree with this. This democracy is a sham, it’s all wrong.’”

Lucas has never been a socialist. Star Wars is what it is because he was living through revolutionary times in which young people were increasingly faced with a choice between two sides, empire and rebels. But this makes his story all the more effective: a call for rebellion from a mainstream liberal guy in extraordinary circumstances.

We talk about ‘radical’ politics. But as the actor and activist Ellen Page says, “We need to stop claiming the political activists are ‘radical.’ The people who are fucking radical are the people who want to keep destroying our water and our topsoil and our air in order to give a few people billions more dollars.”

In our world, as in Star Wars, it’s the empirists who are the extremists. Being ‘radical’ is now the only way to be responsible. We face a planet-destroying empire – ideologically-driven, deceptive and dangerous. Our most likely path is toward the dark side: violent, exploitative, racist and authoritarian (I’ll discuss the lure of the dark side in the next post). Unless we change course, unless we rebel against the system that’s leading us there. And who is the rebellion? It’s whoever realizes we can’t go on like this, that compromise and accommodation and conciliation with empire is no longer possible.

Paradoxically, this is why, along with its fantasy setting and sheer entertainment value, Star Wars is often dismissed as childish: the criticism allows us to distance ourselves from taking action, from, as Denis Wood (not a professional critic, but an early and insightful fan of the series) suggested, “real living, consulting your feelings instead of your attitudes, your being instead of your position, your sense of humanity instead of your career line.” The series says that, despite everything, we can rip out our constraining bolts and challenge the system. And an unjust universe has no place for pessimism and passivity, since as George Lucas argued:

“If you can’t do anything about the Empire, the Empire will eventually crush you ...To not make a decision is a decision... What usually happens is a small minority stands up against it, and the major portion are a lot of indifferent people who aren’t doing anything one way or the other. By not accepting the responsibility, those people eventually have to confront the issue in a more painful way – which is essentially what happened in the United States with the Vietnam War.”

In the next post I’ll discuss how Star Wars represents generational conflict – a kind of civil war that, as in the 1960s, is once again relevant today.

Welcome to the Rebellion: A New Hope in Radical Politics, will be published in June 2020 by Zero Books. You can pre-order your copy now at:

US: Amazon.com, Barnes and Noble, Books-A-Million, Indiebound

UK: Amazon.co.uk, Zero Books, Waterstones, Foyles, Blackwells

Rest of the world: Chapters/Indigo, Booktopia, Book Depository, Goodreads

A FREE preview of the introduction to the book is available on Amazon.

Why the politics of Star Wars still matters (part 3): “The Death Star will be in range in five minutes”

This is a series of posts drawing on my forthcoming book Welcome to the Rebellion: A New Hope in Radical Politics (published in June 2020 by Zero Books).

The previous post considered how Star Wars dramatizes the ways in which authoritarians use inequality and injustice to manipulate their way to power. This post suggests that the saga contains an even darker metaphor in its depiction of empire, one that threatens our very existence.

From its first appearance, the Death Star lodged in our collective imagination as a symbol for epic destructive capability. As such, it’s a pretty good metaphor for an oppressive, exploitative, crisis-ridden globalized industrial capitalism that, left unchecked, seems destined to destroy us.

For the first time in human history, we have planetary scale systems, in energy, trade, and now in digital data – empires in our own world. The problem is, they’re unsustainable.

The greatest crisis we face is of course climate change and environmental destruction. In 2009, an international group of experts identified nine interconnected “planetary boundaries” that underpin the stability of the global ecosystem. Three boundaries have already been passed (climate change, biodiversity and the nitrogen cycle) and two are coming close to being passed (ocean acidification and the phosphorus cycle). Worse, all of the trends are speeding up, a ‘great acceleration’ beyond known environmental limits.

To the Death Star of our current system of industrial capitalism, we are Alderaan. Or maybe Alderaan isn’t the best (Star Wars-based) analogy. More likely, we’re creating Tatooine – formerly a lush planet of forests and oceans, now a baking, barren, brutal desert.

We’ve crossed over a threshold into an age of systemic risk, in which population pressures, natural resources, climate, politics and the economy will interact in predictable and unpredictable ways to create global crises which feed on and magnify each other. It is a crisis of crises, what James Howard Kunstler has called the long emergency.

To take one example, the age of climate wars has begun. Extreme weather is bringing conflict, humanitarian crisis and state failure. Mass migration and refugees will continue to increase. The climate crisis could lead to ten times more refugees from the Middle East than the 12 million who fled during the past few years of upheaval and turmoil. The hard right has skillfully manipulated and inflamed a backlash over this crisis. By denying climate change and blocking action, they’ll make mass forced migration more likely and then reap the benefits by whipping up hatred against the tide of human misery.

Star Wars wasn’t directly inspired by the emerging environmental movement. But as I argue in my book, the story did come out of the 1960s new left, alongside other cultural influences, and new left thinking was one strand of a growing global consciousness, ranging across the then still emerging environmental movement, Eastern philosophies, and critiques of Western materialism, colonialism and militarism (of course, a crucial inspiration for the saga was the war in Vietnam).

There are certainly elements of environmental critique in Star Wars. Witness the Empire’s attachment to technology for colonization and domination, and the way the story dramatizes how technology can become our master rather than our servant. Most obviously, there’s Darth Vader, who embodies an estrangement from any authentic self, an unearthly interface between a damaged humanity and technological life support. As Canaan Perry suggests, the Empire is subsumed by its own technological constructions, whereas the Rebels use and adapt technology but are not slaves to it.

Technology is set to dominate our lives in the future even more than it does now. Like the difference between the Empire and the Rebels, whether it enslaves or frees us depends on in whose interests it’s used. Automation and artificial intelligence (AI) could liberate us from work and provide a better standard of living for everybody. But in the hands of empire, they will mainly be used to benefit corporations and increase inequality.

As Nick Srnicek has described it, the fundamental foundations of the economy are rapidly being carved up among a small number of monopolistic digital platforms, dubbed ‘platform capitalism’. The Sarlaac Pits of this new economy are companies like Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix and Google, suitably known as the FAANGs. They’re imperial in their design, dependent on insatiable growth to seize and consolidate monopoly power.

Welcome to the age of ‘surveillance capitalism’. As Shoshana Zuboff describes it, this is the latest phase in capitalism’s evolution – from making products, to mass production, managerial capitalism, through services to financial capitalism, and now to the exploitation of behavioural predictions covertly derived from the surveillance of users offered ‘free’ products. These corporations monopolize data science and dominate machine intelligence. They also have vast reserves of capital.

As Zuboff suggests, whereas most democratic societies have at least some degree of oversight of state surveillance, we currently have almost no regulatory oversight of its privatized counterpart. Like any empirists, the first surveillance capitalists conquered by declaration: they simply declared our private lives to be theirs for the taking.

Star Wars also suggests what underlies such systems. We face many crises, but really, it’s just one crisis. At root it’s not economic or political but philosophical and psychological. It is empirism: the compulsion to dominate people, nature and thought. It’s the Sith’s individualistic ‘morality’ of acquisition.

As campaigner and activist Charles Derber (Welcome to the Revolution) puts it, in earlier centuries capitalism freed millions from ancient forms of bondage and want. Today’s capitalism creates and perpetuates isolation and insecurity, extreme inequality, corporate power, billionaire rule, militarism, repression, climate change, environmental destruction and exclusion.

But this is reaching its natural end. Limitless extraction and growth are not possible on a finite planet. As Yuval Harari notes, our profound dilemma is that: “[E]conomic growth will not save the global ecosystem – just the opposite, it is the cause of the ecological crisis. And economic growth will not save the technological disruption – it is predicated on the invention of more and more disruptive technologies.”

As I’ll discuss in the next post, Star Wars is about taking a stand. Being apolitical today, especially ignoring the Death Star that’s looming over our planet, has an even greater cost than when George Lucas was first developing his saga. The walls of the trash compactor are closing in and we’re all trapped inside. Yes, empire privileges some of us with comforts, but as Han Solo said (though he meant it a different way), “What good’s a reward if you ain’t around to use it?”

Welcome to the Rebellion: A New Hope in Radical Politics, will be published in June 2020 by Zero Books. You can pre-order your copy now at:

US: Amazon.com, Barnes and Noble, Books-A-Million, Indiebound

UK: Amazon.co.uk, Zero Books, Waterstones, Foyles, Blackwells

Rest of the world: Chapters/Indigo, Booktopia, Book Depository, Goodreads

A FREE preview of the introduction to the book is available on Amazon.

Why the politics of Star Wars still matters (part 2): “The Imperial Senate will no longer be of any concern to us”

This is a series of posts drawing on my forthcoming book Welcome to the Rebellion: A New Hope in Radical Politics (published in June 2020 by Zero Books).

The first post in this series discussed the importance in politics of owning rebel stories. This post discusses what happens when authoritarians manipulate popular discontent for their own ends.

To a number of critics at the time and to many ever since, rather than being political, Star Wars (A New Hope) provided a fantastical distraction from politics. By the mid-1970s, Americans had recently learnt that their government was a cancerous conspiracy (Watergate) and that, against the country’s self-image, they were hated imperialists (the Vietnam War). Despite President Gerald Ford pardoning the corrupt Richard Nixon and declaring that “Our long national nightmare is over,” many Americans thought they recognized the foul stench of a rotting republic all around them.

And so, a spectacular space opera must have seemed like some much-needed light relief. But really, Star Wars was deeply political from the beginning, and very much reflected its times. It’s a fable rooted in the 1960s American new left, a warning about creeping authoritarianism, and a beacon of new hope to rebels everywhere.

George Lucas acknowledges that he wrote Star Wars because he thought that society was in need of myths, but not as a distraction from what was going on. Star Wars is contemporary folklore about the rise and defeat of fascism (and rise again, as the sequel films – the ones made under Disney – dramatize).

Conservative commentators have tended to grasp what Lucas was up to far more readily than those on the left. For example, Arthur Chrenkoff has warned conservatives that Star Wars has long been a radical left ‘fantasy’:

“[T]he... evil Empire is [the] United States, and the heroes, the good guys that we, the viewers, are meant to root for, are the communist guerrillas... [T]he American Empire was a quasi-fascistic, semi-dictatorial, highly aggressive and militaristic polity in the grip of “the military-industrial complex” and “the power elites”, suppressing dissent and subjugating minorities at home, while continuously invading poor Third World countries to crush their national aspirations in the interests of the American corporations and the American war machine.”

Well, indeed.

George Lucas’s political perspective was influenced from the 1960s new left, which rejected the anti-democratic nature of ‘old left’ bureaucratic Marxist-Communist parties as well as contemporary capitalism and conventional centre-left politics (I’m not suggesting that Lucas was a new leftist, rather he was a liberal guy living in tumultuous times). The new left was anti-imperialist and emphasized grassroots democracy. In the US, the movement was most associated with anti-war college-campus protests, including Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), and the Free Speech Movement. The latter started during the 1964-1965 academic year on the campus of the University of California at Berkeley (Lucas attended USC Film School in the early 1960s and re-enrolled as a graduate student from 1967-1968. He claimed of his time at university, “I was angry at the time, getting involved in all the causes”).

A New Hope throws us into the midst of the galactic civil war. But let’s go back earlier in the chronological story (as told later in terms of the films), to how the Empire came to be. The Star Wars prequels have been derided by many critics and fans, though they’ve undergone a re-evaluation of late. But their most important contribution is to dramatize, however shakily, that the Empire didn’t arise outside of the Republic but grew within it. As Lucas has explained:

“When I first started making [A New Hope], it was during the Vietnam War, and it was during a period when Nixon was going for a third term – or trying to get the Constitution changed to go for a third term – and it got me to thinking about how democracies turn into dictatorships. Not how they’re taken over where there’s a coup or anything like that, but how the democracy turns itself over to a tyrant.”

The political story of the prequels is how the Sith manufacture a crisis and seize on the desire of a frustrated public for strong leadership to master the chaos. Chancellor Palpatine is granted emergency powers that open the door to militarization, repression including the liquidation of the Jedi, and the establishment of dictatorship.

As Anne Lancashire notes, the prequels emphasize the corrupting influence of militarism on democracy, a major new left theme. In Attack of the Clones, war is depicted as a tool supported by profit-seeking big business, the means by which manipulative leaders achieve power by exploiting fear and greed.

And underlying all this – not prominent enough in the films but it’s there – is rampant inequality. While the Galactic Republic afforded political representation to hundreds of worlds and star systems for the first time, much inequality and exploitation remained, particularly of the outlying Outer Rim territories compared to the central Core Worlds (including the Republic’s capital of Coruscant). In our world, as in the saga, these inequalities set in train the events leading to authoritarianism.

As Nader Elhefnawy describes it:

“Here we have a vast republic in which Big Business in its greed is trampling on everything and everyone, unrestrained by the government, which has had its courts and its legislators corrupted... Meanwhile, the most backward forms of exploitation and oppression continue to flourish – or perhaps, even resurge – at the margins (like slavery on Tatooine), and the whole system appears increasingly decrepit. Naturally the mess creates openings for reviving violent, irrational, reactionary elements (the Sith) that present themselves as partners to an economic elite determined not to compromise with the rest of society.”

George Lucas was once asked what one thing he hoped fans understood about his most famous story. He replied, “I only hope that those who have seen Star Wars recognize the Emperor when they see him.” But it’s also a warning about how real injustice provides an opportunity for authoritarians. When Palpatine is still a senator, he says, “The Republic is not what it once was. The Senate is full of greedy, squabbling delegates. There is no interest in the common good.” His promise is to make the Republic great again, to drain the swamp of the Galactic Senate, and serve the interests of the galaxy’s citizens. But that’s not his real agenda.

As we later learn, he’s secretly engineered the blockade of the planet Naboo, part of his plot to seize power. The planet’s (elected) Queen Amidala pleads in front of the Senate for help. When she is rejected, she calls for a vote of no confidence in Chancellor Velorum, leaving the way clear for Palpatine to replace him. As Amidala later regrets, “So this is how liberty dies ...with thunderous applause.”

We have been warned – by history, and, it turns out, by our most popular piece of modern folklore.

In the next post, we’ll examine how empire threatens not only democracy, but our very existence.

Welcome to the Rebellion: A New Hope in Radical Politics, will be published in June 2020 by Zero Books. You can pre-order your copy now at:

US: Amazon.com, Barnes and Noble, Books-A-Million, Indiebound

UK: Amazon.co.uk, Zero Books, Waterstones, Foyles, Blackwells

Rest of the world: Chapters/Indigo, Booktopia, Book Depository, Goodreads

A FREE preview of the introduction to the book is available on Amazon.

Why the politics of Star Wars still matters (part 1): “It’s not a story the Jedi would tell you”

This is a series of posts drawing on my forthcoming book Welcome to the Rebellion: A New Hope in Radical Politics (published in June 2020 by Zero Books).

This first post is about the importance of rebel stories.

If your immediate reaction is to cry “leave politics out of Star Wars!” (or the other way around), you’re welcome to enjoy your space favourite space opera however you like (it’s a big galaxy, after all). But there’s politics in this epic story of civil war, a faltering republic, the rise of empire, and of course rebellion – undeniably in its inspirations (as we’ll discuss in this series), and I’d argue, in its continued relevance today. If your politics is different from mine, this is only one interpretation, and again, you’re entitled to your own (plenty of libertarians love Star Wars, and I can absolutely understand why).

My book starts in a paradox, at least it’s a paradox from my perspective. The political story of our times is that a rebellion is underway against elites and their greedy global order. It is amassing support from ordinary people, who feel marginalized and unheard. In a way they haven’t felt for a long time, people feel an increasing sense of power and belonging. They are back at the centre of the story, and elites fear them.

But of course, they’re part of a regressive revolt, led by the right, by Donald Trump in the United States, conservative hard Brexiteers in the UK, the far right across Europe, and authoritarians across the world. How is it that such a story, a rebel story, which should naturally be owned by the left, has been seized by the right, and what do progressives and the left need to do to reclaim this story?

I’ve written a book on the relevance of the politics of Star Wars today because the saga, and the universe that’s expanded from it, is about many contemporary issues: freedom, democracy, oppression, exploitation, hope and rebellion. But the first thing Star Wars is about is stories and their power to shape politics.

In particular, it’s rather good at depicting how authoritarians use stories to serve their own ends. Senator Palpatine wouldn’t have been able to take over the galaxy without telling stories, that’s where his dark powers really lay. Similarly, the right understands that politics lies downstream from culture (Andrew Breitbart, the right-wing nationalist ideologue, said that), and culture is about stories.

For decades, in countries such as the US and UK, many people have seen their wages stagnate while the rich have got massively richer. They have seen their towns and cities decline, their hearts ripped out by globalization, outsourcing, automation and a lack of care. They have seen corrupt political elites doing the bidding of corporations. And they have been told a story of ‘trickle-down’ economics which ended in a financial crisis, for which no-one was held accountable. It’s not that, as often stated in the mainstream media, people ‘feel’ left out. They are left out. No wonder they were ready for a new story, and they were so willing to shake up the status quo.

Now, I’d argue that the programs and policies being driven through by the right will benefit only the already rich and powerful. Nonetheless, the story people have been told – of their subjugation and defeat, and their revolt and rise to victory – speaks to them. Our economic system increasingly says to people, ‘you are nobody’. These stories tell people that they matter. They draw on the behaviour and self-interest of politicians, domineering corporate interests and the hopelessness felt in forgotten people and places. Not only do these stories identify the problems and the villains, they cast ordinary people as overmatched heroes: regular folk doing battle against mendacious elites. They allow people to see themselves as rebels, the imperilled remnants of human freedom, taking a stand against sadistic all-powerful global forces (that would be the ‘empire’) who are forever tightening the screws.

Stories don’t have to be manipulations, however. Even when they are selective, which stories necessarily are, they can express deeper truths and help us to face them. The problem is, the left seems to have forgotten how to tell good tales.

The left used to have its stories, its adventures, its victories and defeats involving individual and collective struggles. But ‘scientific’ socialism pushed aside storytelling socialism, liberal ‘pragmatism’ looks down on storytelling as dangerous populism, and now, with postmodern-influenced cultural theory, stories themselves are said to be dead. And so instead of telling its own stories, the left often spends more time trying to deconstruct the right’s stories. But as environmental campaigner and journalist George Monbiot suggests, you can’t take away someone’s story without giving them a new one. Reactionary myths need to be overcome by emancipatory myths.

For these and other reasons, the left has neglected that it ‘owns’ the most popular rebellion story of our age – one that is political but also personal, democratic, collectivist rather than individualist, emotional and hopeful, a wildly popular saga, arguably the most successful story of our time.

It's more important than ever that we can tell popular stories about the need to stand against empire. We need to believe that many more people are ready to join the rebellion than we’re often told. And among other things, we need to claim popular culture to do it.

It means something that our most popular modern myth is a radical left story about fighting fascism. Contrary to postmodern cultural pessimism, the continuing popularity of stories such as Star Wars suggests the potential for a popular radical politics which is anti-authoritarian, pluralist, participatory, democratic and humane. From its roots in the 1960s new left (as I’ll describe in the next post), Star Wars still speaks to so many people today, including new generations of fans. It indicates a widespread desire to reject nihilism and despair, and to struggle against oppression and for liberation.

Yes, it’s a space fantasy, but even so, go with it and Star Wars can be used to illuminate the dark times in which we live. It also suggests that if we tell the right stories, we can welcome many more people to the rebellion and the fight for a better world.

Welcome to the Rebellion: A New Hope in Radical Politics, will be published in June 2020 by Zero Books. You can pre-order your copy now at:

US: Amazon.com, Barnes and Noble, Books-A-Million, Indiebound

UK: Amazon.co.uk, Zero Books, Waterstones, Foyles, Blackwells

Rest of the world: Chapters/Indigo, Booktopia, Book Depository, Goodreads

A FREE preview of the introduction to the book is available on Amazon.

A virtual gallery of Star Wars political art (part 3)

As I’ve come across them, I’ve been posting examples of Star Wars-inspired political art on Instagram (@michaelharrisbooks). In previous posts here and here I’ve been republishing some of my favourites. If you’ve seen other examples (or can help with some of the artist attributions I haven’t been able to find), do let me know.

Artist unknown.

Orlando Arocena again, making the link between the saga and the Vietnam War by echoing the posters for Stanley Kubrick's 1987 movie Full Metal Jacket.

Artist unknown.

Artist unknown.

Another Hong Kong protest poster, artist unknown, via Telegram.

Unsurprisingly, Star Wars images have often been used by the Resistance, as this example demonstrates.

Artist unknown.

And because I can, here’s the cover image from my forthcoming book. Image by Louie dela Cruz.

A virtual gallery of Star Wars political art (part 2)

As I’ve come across them, I’ve been posting examples of Star Wars-inspired political art on Instagram (@michaelharrisbooks). Starting with a previous post, I’ve been republishing some of my favourites. If you’ve seen other examples (or can help with some of the artist attributions I haven’t been able to find), do let me know.

Julian Callos @juliancallos contributed this piece, titled "Rebel", to the Art Awakens show in Los Angeles in 2015, which featured over 100 brand new pieces of Star Wars inspired art. The works were auctioned for charity.

Artist unknown.

Artist unknown, via @StandwithHK on Twitter.

Bob Al-Greene @bobalgreene drawing on Shepard Fairey's Obama ‘Hope’ poster. See: bobalgreene.com https://www.behance.net/gallery/52834649/Rogue-One-Hope-Posters

Artist unknown, created as part of the Hong Kong protests.

Another piece from Hong Kong, this time from #rebelpepperwang (@RebelPepperWang on Twitter).

A virtual gallery of Star Wars political art (part 1)

As I’ve come across them, I’ve been posting examples of Star Wars-inspired political art on Instagram (@michaelharrisbooks). In this post and the next few posts I’ll republish some of my favourites. If you’ve seen other examples (or can help with some of the artist attributions I haven’t been able to find), do let me know!

Cedric Delsaux, from his Dark Lens series.

The Dark Side of Liberty Darth Vader t-shirt by Allriot

Orlando Arocena makes the link between the saga and the Vietnam War by echoing the posters for Stanley Kubrick's 1987 movie Full Metal Jacket.

More examples of Star Wars political art in the next post.

Read the Prologue to Welcome to the Rebellion!

My second book, Welcome to the Rebellion, is published at the end of June/beginning of July (“Coming to your galaxy this summer”, as they say). But you can read the prologue here.

My second book, Welcome to the Rebellion, is published at the end of June/beginning of July (“Coming to your galaxy this summer”, as they say). But you can read the prologue here - and if you like what you read, please consider ordering from all of the usual places!

Welcome to the Rebellion is published in June 2020 by Zero Books - order your copy now at:

US: Amazon.com, Barnes and Noble, Books-A-Million, Indiebound

UK: Amazon.co.uk, Zero Books, Waterstones, Foyles, Blackwells